On Sept. 26, 2014, more than 100 students from a rural teachers’ college in the Mexican town of Ayotzinapa set out to neighboring Iguala. They were traveling there for the commemorative march of the Mexico City student massacre of 1968. Forty-three of them were never seen again after that night.

According to the Mexican government, Iguala’s mayor ordered local police to arrest the students, and after confrontations with local police, six people died, 25 more were injured, and 43 were handed over by the police to a local narcogang. Three of the gang members confessed to murdering the students and burning their bodies in a nearby dumpster. An independent forensic research team’s conclusions recently disputed this version of events, calling it “scientifically impossible.”

The events surrounding Ayotzinapa made the link between the narcogangs and the government, which had seemed obvious but vague until then, impossible to ignore. They shocked the Mexican population and motivated thousands to take to the streets in protest. But after Ayotzinapa, protests alone could not do what art does: make the invisible visible. Protests for Ayotzinapa needed to evoke, narrate, and create in order to recreate what was now missing and to materialize an unprecedented level of rage, pain, and discontent.

Relatives carry photos of some of the 43 missing students of the Ayotzinapa teachers’ training college during a protest to mark the 11-month anniversary of their disappearance in Mexico City, Aug. 26, 2015.

Photo by Henry Romero/Reuters

Photo by Edgard Garrido/Reuters

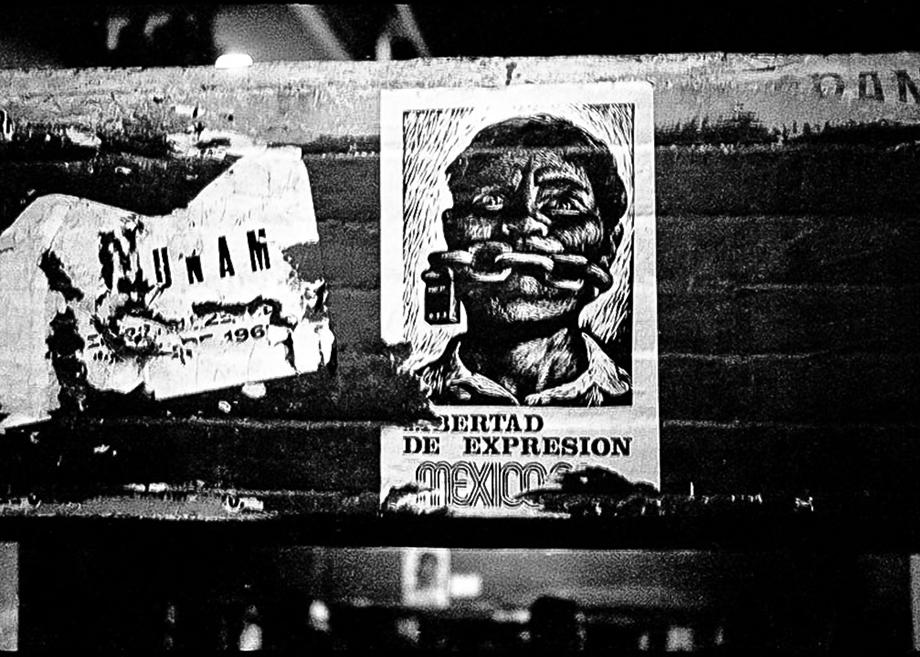

Intertwining art and activism is a strong Mexican tradition, ranging from the propagandistic muralism of the 1930s to the art collectives of the 1970s and 1980s, which used their work as political strategies in the service of popular movements.

Image courtesy Pedro Meyer

In the 1990s, artists responded to a devastating financial and political crisis with bitingly critical works, like Daniela Rossell’s Rich and Famous, a series of portraits of Mexico’s wealthiest women posing in their ostentatious homes. After President Felipe Calderón launched a military campaign against el narco in 2006, Mexican artists like Teresa Margolles, Carlos Amorales, and Enrique Ježik exposed the death toll the government was trying to conceal through gory artworks exhibited all over the world.

Photo courtesy Enrique Ježik

After the disappearance of the Ayotzinapa students, banners and graffiti again populated the streets of Mexico as it did in ’68. Similarly, in an extension of the cities’ walls, hashtags like “#TodosSomosAyotzinapa” (#WeAreAllAyotzinapa) and “#NosFaltan43” (#WeAreMissing43) took over social media. The most striking of these was “#FueelEstado” (#ItWastheState), because it not only established the responsibility of the state but shattered the myth that the government and the narcogangs worked independently from each other.

Photo courtesy Colectivo Rexiste

After a demonstration of almost 50,000 people on Oct. 22, 2014, the collective Rexiste painted the phrase on Mexico City’s main square, the Zócalo, which faces the National Palace. Photos of this demonstration took over Twitter and #FueelEstado became a trending topic. It was later seen on the floor of National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City, on a church façade in Oaxaca, on a field in San Cristóbal de las Casas, and on walls around the world.

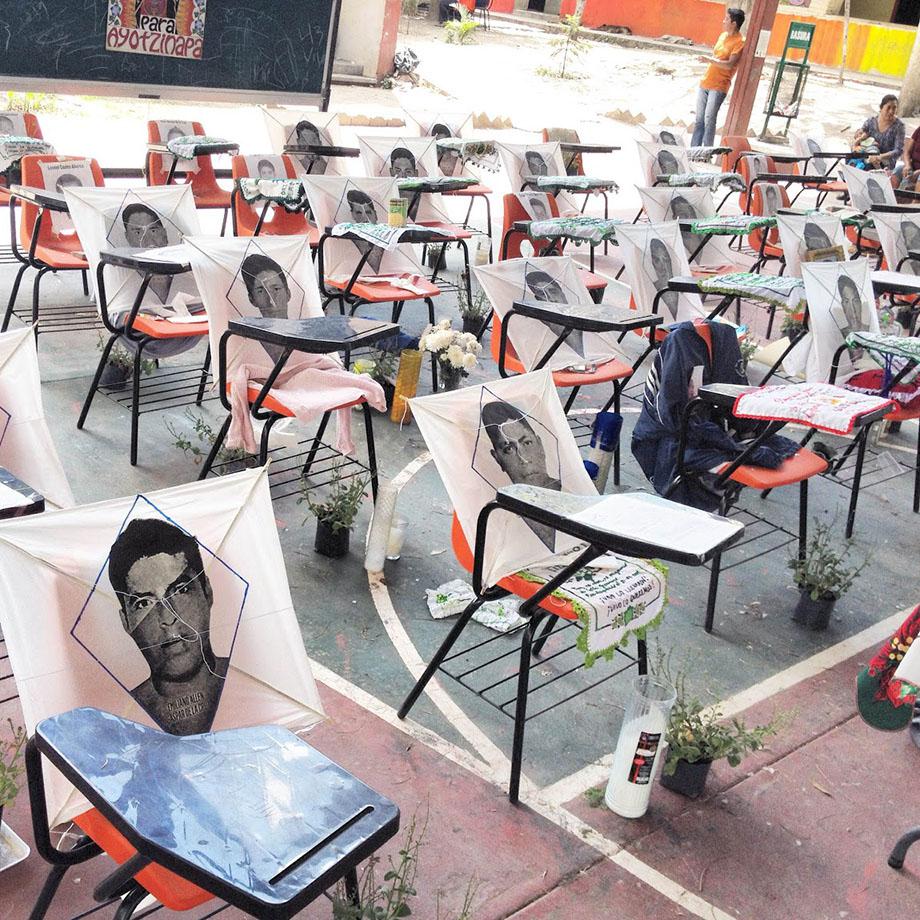

The responses to Ayotzinapa poured in from places like Paris, New York, and London. One notable recurring image was the arrangement of 43 empty school chairs to evoke the missing students, which started in the courtyard of the teachers’ college in Ayotzinapa and was replicated in cities worldwide, in classrooms at New York University, Princeton, universities in Tegucigalpa, Honduras; Rome; and in public squares in Oslo, Norway; Paris; and Santiago de Chile.

Photo by Tryno Maldonado

Demonstrators and students throughout Mexico and abroad also mimicked the Siluetazo in Argentina in 1983, which attempted to make the military dictatorship’s forced disappearances visible. As in Buenos Aires, passers-by laid on cardboards for others to draw their silhouettes, and the cardboard figures were later pasted on walls throughout the city.

Photo courtesy Rosario Ateaga

One of the strongest reactions to Ayotzinapa happened spontaneously, on Nov. 20, 2014, in Mexico City. Almost 100,000 people marched toward the Zócalo in what became one of the biggest demonstrations in Mexico’s history. A few hours later an effigy of President Peña Nieto was burned to the ground in a subversive version of the “burning of Judas,” an annual Easter ritual. This action, which happened after the attorney general broadcasted his unconvincing account of the events in Iguala, showed not just a deep state of mourning but also an intense rage against Mexican authorities. Nov. 20 also marks the anniversary of Mexico’s revolution, making the association with political insurrection inevitable.

Photo by Bernardo Montoya/Reuters

Today’s fear is that Ayotzinapa will be buried in oblivion together with hundreds of Latin-American struggles. After one year, protests have declined, but artists are still responding. Mexican artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer created a face-recognition software, Level of Confidence, “trained to tirelessly look for the faces of the disappeared students,” according to the artist’s statement.

The outrage remains, as do the 43 empty chairs in the courtyard of the Raúl Isidro Burgos’ school in Ayotzinapa. To this day, parents bring flowers and candles to their sons’ vacant seats.

Also in Slate, Will Obama Press Mexico’s President for Answers on the Disappearance of 43 Students?