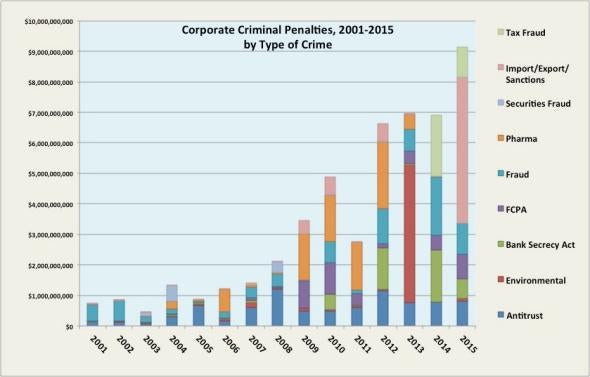

“We’re going to wait and we’re going to wait and we’re going to wait until they feel the pain, until they start to bleed,” says Steve Carrell’s character in The Big Short, about Wall Street and the buildup to the 2008 financial crisis. After waiting for years, are the feds now making banks feel any pain? Fines in the millions and billions of dollars made headlines again and again in 2015, as the Department of Justice set new records in prosecutions of wrongdoing corporations. In 2015, the feds finally prosecuted banks, and a lot of them, something that critics rightly accused the DOJ of failing to do in the past. More banks than ever before paid sums never seen before. Corporations paid more than $9 billion in penalties to federal prosecutors last year, and they paid billions more to regulators and others.

Nevertheless, we need to keep asking whether this strategy of chasing dollars rather than changing practices and prosecuting executives makes any sense. In the past decade, data I have collected show that federal prosecutors have set new records each year in corporate fines. For all their success and zeal, however, it’s not clear that fines alone are stopping bad actors on Wall Street.

There is no corporate crime registry in the United States. One difficulty in assessing the work of prosecutors in these cases is that many of the largest corporations settle out of court, avoiding formal sentences that could be tracked by the U.S. Sentencing Commission. With invaluable help from the University of Virginia Law Library, over the past decade I amassed a collection of hundreds of out-of-court deals between federal prosecutors and corporations, as well as an even larger archive of plea agreements that did result in corporations getting convicted in court. As part of this tracking of corporate prosecutions, I also collected detailed information about the fines and other penalties paid, the terms of the agreements requiring independent monitoring and compliance reforms, and whether any individual officers or employees were prosecuted. Looking down the list of companies, you quickly see that the major banks, like Barclays, Credit Suisse, HSBC, JPMorgan, and UBS, were not getting convictions, but instead were largely inking out-of-court deferred and nonprosecution agreements. Only in recent years did banks start to plead guilty. The rise in the dollar amounts paid by corporations over the past decade has also been extraordinary; billion dollar criminal fines were simply unheard of 10 years ago.

Chart by Brandon L. Garrett*

What was different in 2015 was that so much of the money paid by corporate targets came from banks: almost $7 billion of the $9 billion in total penalties paid by prosecuted companies. To be sure, the bulk came from a single record-shattering case involving the French bank BNP Paribas, which paid more than $4 billion to prosecutors (and many billions more to regulators and local prosecutors). But there was also the $625 million paid by Deutsche Bank in an antitrust case, the $641 million paid by Commerzbank, and $156 million paid by Credit Agricole in money-laundering and export-violation cases. Scores of Swiss banks collectively paid almost $1 billion in tax prosecutions. The only really big settlement that didn’t involve a bank was the $900 million paid by GM.

A remarkable number of banks, 80 of them, finalized cases with federal prosecutors. Most were Swiss banks that settled out of court as part of a DOJ Tax Division program designed to incentivize them to come clean or face the music. Next year we will see still more cases with less-cooperative Swiss banks that won’t get such lenient deals. More mammoth bank cases lumber along in the courts; last spring, several major banks, including Wall Street giants JPMorgan Chase and Citicorp, agreed to plead guilty in cases relating to foreign-exchange currency manipulation. Those cases have not resulted in sentencing yet, but when they do, prosecutors will rake in $5 billion more in fines.

Is there still a concern that banks remain not just “too big to fail”—so important to the economy that they’ll be bailed out should they become insolvent—but also “too big to jail,” seen as so vital that their crimes will be excused and their employees untouched by criminal charges? In 2014, then–Attorney General Eric Holder said “There is no such thing as too big to jail,” because no bank “should be considered immune from prosecution.” One would hope not, but the concern isn’t simply with an outright refusal to prosecute bankers, but with prosecutions that are overly lenient when they do happen and banks’ overall lack of accountability. Very few financial institutions faced prosecutions in decades past. Prosecutors are now starting to insist on guilty pleas and criminal convictions in the largest bank cases. Then again, prosecutors also have settled cases with several major banks repeatedly in recent years. Given a high degree of recidivism among major banks—take UBS, whose rap sheet includes a pending guilty plea, a prior 2012 nonprosecution agreement that the Department of Justice “tore up” in 2015 on account of UBS violating it by committing more crimes, added to prior prosecutions in 2011 and 2009—one wonders what impact the compliance programs and corporate monitors are actually having, and whether these prosecutions are actually changing any underlying culture of rule-breaking.

One possible explanation: Banks pay the fines, but bankers don’t usually do any time. I have found that among the 66 cases of financial institutions that received deferred or nonprosecution agreements from federal prosecutors from 2001 to 2014, only 23 of them—33 percent—had any employees prosecuted. Unlike banks, individuals can literally be put in jail. Federal district judge Emmett Sullivan, considering a deferred prosecution agreement with Barclays, asked in 2010 why “no one goes to jail, no one is indicted, no individuals are mentioned as far as I can determine … there’s no personal responsibility.” In response to widespread criticism, the DOJ announced new policies last fall intended to sharpen the focus on individuals in corporate crime cases. A Delaware bank, Wilmington Trust, was just indicted and a slew of its officers were charged. The first LIBOR rigging cases went to trial in New York and resulted in convictions of two former traders. To be sure, even if the DOJ policy changes are meaningful, and there is reason to be skeptical based on what has happened in the past, they still do not answer the criticism that bankers should have been targeted after the financial crisis. After then–Attorney General Eric Holder said last spring that prosecutors had 90 days to report back and announce any financial crisis–related charges, apparently none were filed.

When a bank pays a fine, ultimately its shareholders foot the bill, and even the largest eye-catching fines may not compare with the profits made based on risky behavior. Billion-dollar fines send a message that prosecutors are more serious than in the past, and indeed, no comparable prosecutors in other countries are taking corporate crime as seriously as federal prosecutors are in the U.S. But for these prosecutions to have a lasting impact, so that we don’t see the same banks settle cases with prosecutors year in and year out, the banks themselves need to be reformed, better regulated in the first instance, and have their employees and higher-ups be held accountable. When the jury delivered its verdict last December convicting former Massey Coal CEO Don Blankenship of mine-safety violations that led to the deaths of miners, the prosecutor announced, “The jury’s verdict sends a clear and powerful message: It doesn’t matter who you are, how rich you are, or how powerful you are—if you gamble with the safety of the people who work for you, you will be held accountable.” We need verdicts sending a similar message about what happens when bankers gamble recklessly with people’s livelihoods.

Correction, Jan. 13, 2016: The title of the chart in this article originally said it shows the year 1994 to 2015. It shows 2001 to 2015 and has been updated.