Long before Donald Trump began talking about building a wall between the U.S.–Mexico border, Michelle Frankfurter read Sonia Nazario’s book, Enrique’s Journey, a nonfiction account of a boy’s passage from Mexico to the United States in search of his mother.

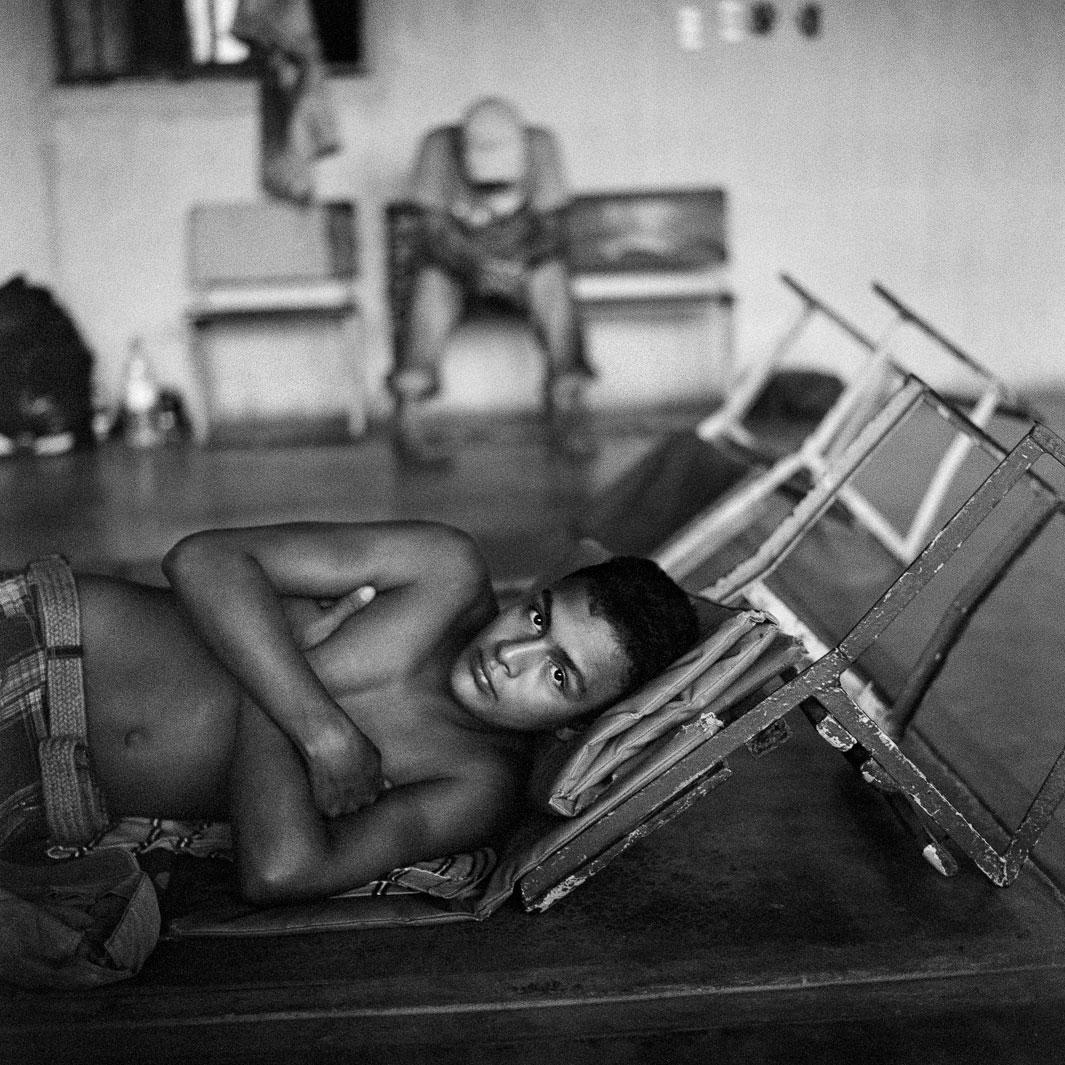

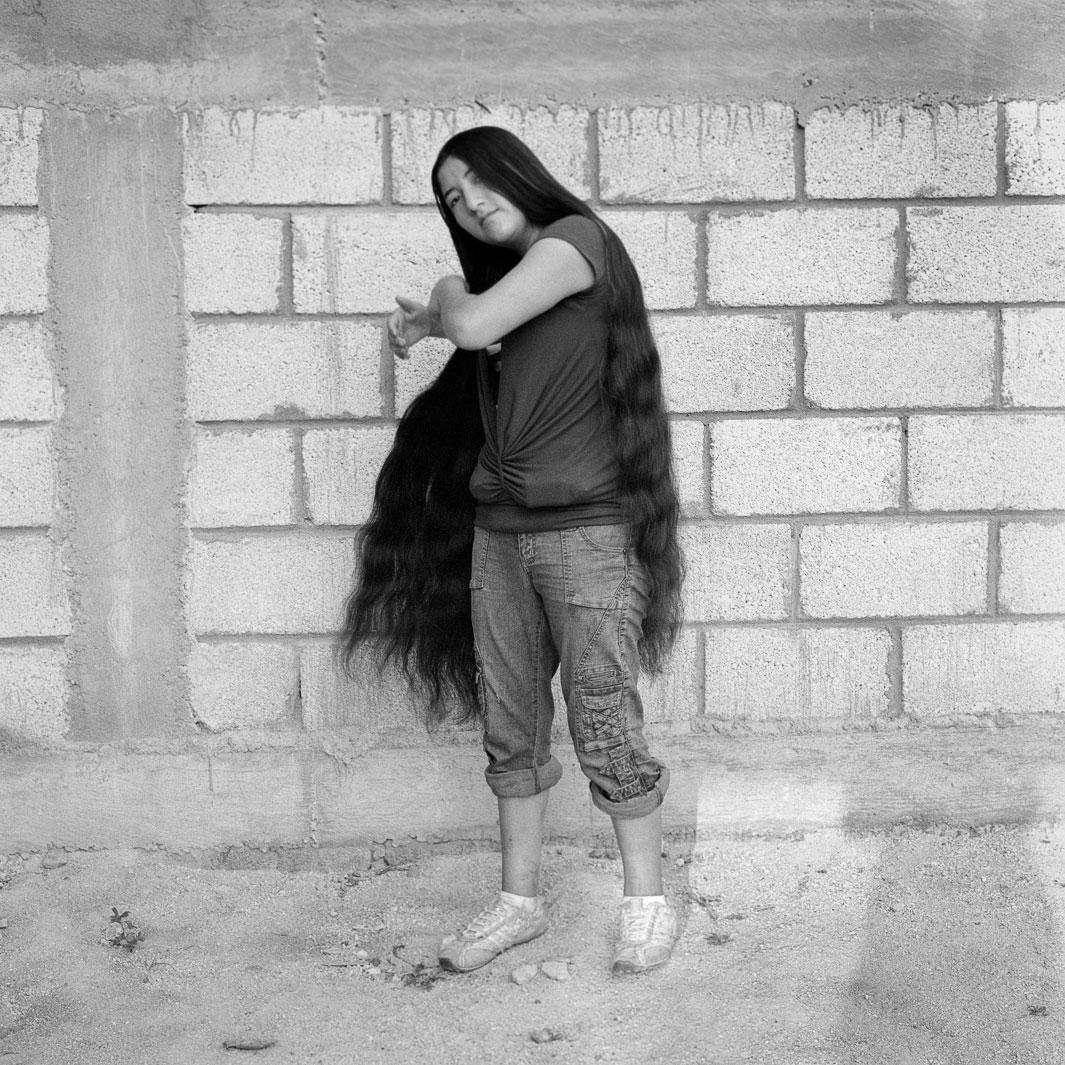

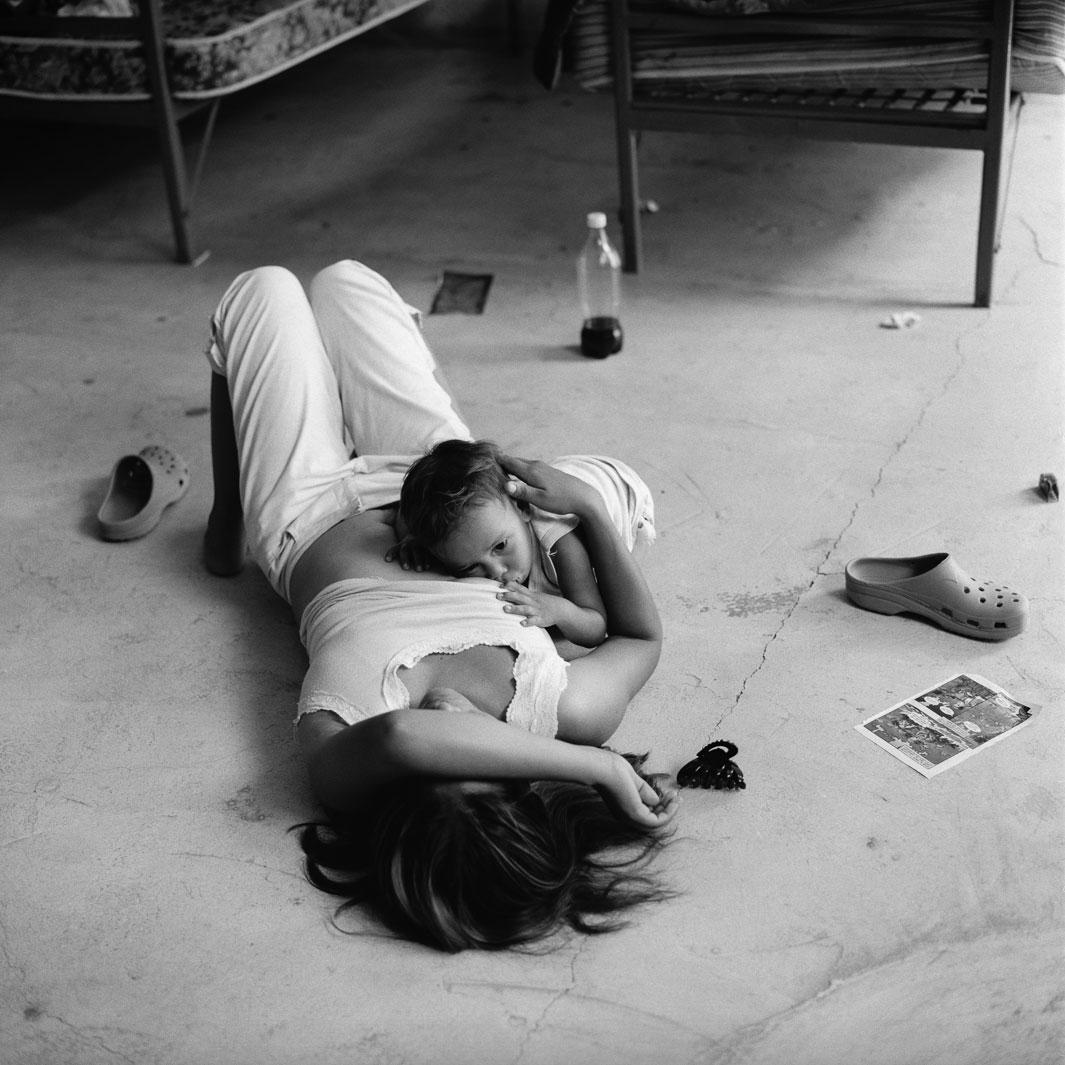

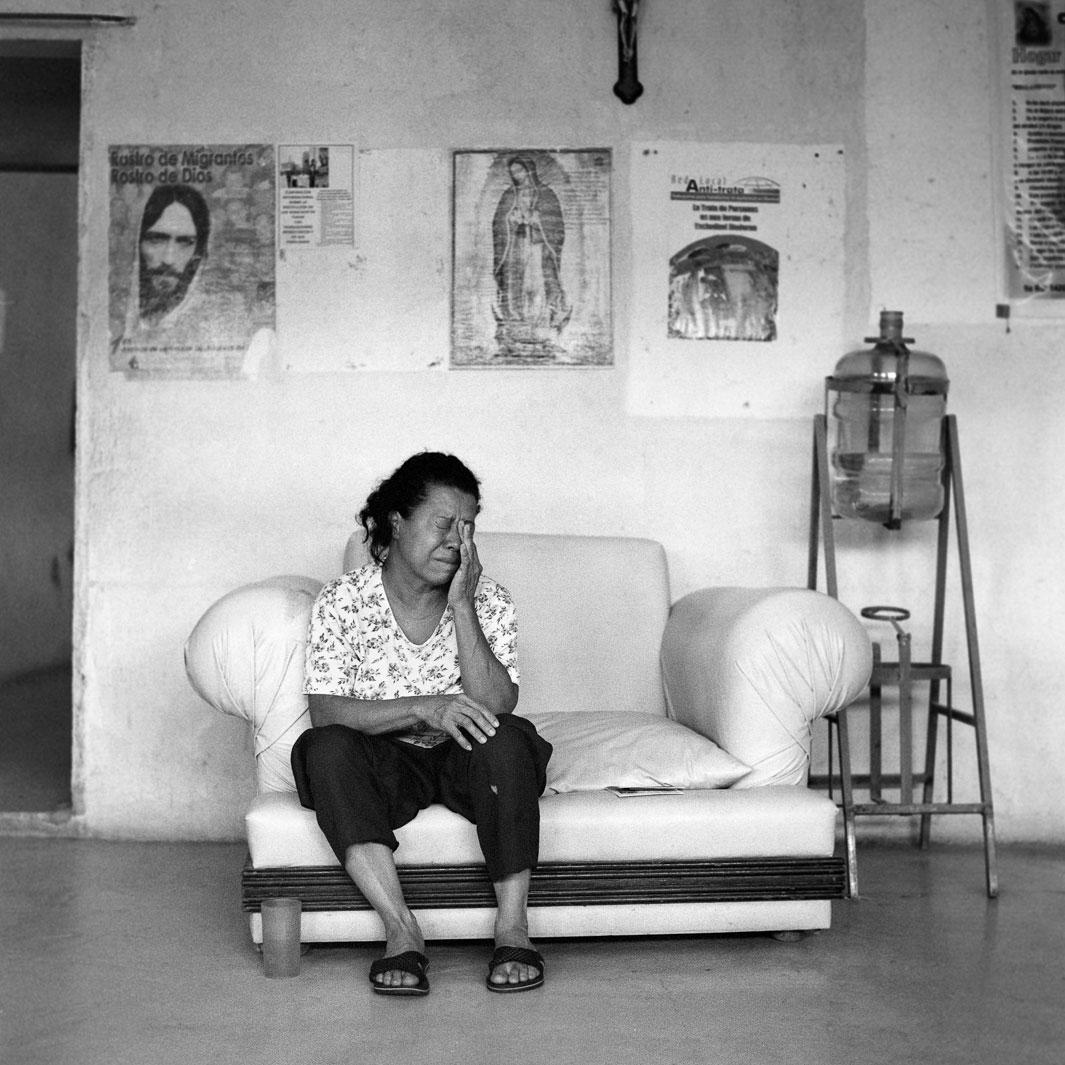

A self-described lover of adventure novels that began with Jack London and continued with Cormac McCarthy, the book resonated with Frankfurter, who had been living, working, and traveling through Central America for 20 years. She calls her series “Destino,” which can be translated from Spanish as both “destination” and “destiny.” Her work is a document about the struggle of people to control their destinies while dealing with adverse circumstances.

“The book had a profound effect on me and read like an adventure tale,” she said about Enrique’s Journey. “I’ve always gravitated to these epic graphic narratives; everything coalesced in my mind [when I read it] and I knew this was the story I wanted to tell.”

Armed with her camera, a bag full of film she had “in [her] vegetable bin,” frequent-flyer miles, and one credit card, Frankfurter took the first of many flights to Mexico City in order to ride the trains with undocumented Central American migrants looking to eventually reach the United States in search of the mythological “American Dream.” The more trips she took, the more the narrative began to unfold, although she feels each photograph tells its own story about her subjects.

“It was a huge story but I felt the storyline was pretty simple,” she said. “I kept the idea of the narrative at the forefront: that this is an epic journey across a hostile landscape and it’s about trying to get somewhere.”

Michelle Frankfurter

Michelle Frankfurter

Michelle Frankfurter

Michelle Frankfurter

Although the trip can be a dangerous one, Frankfurter said gaining the trust of the people she photographed was easy; most were friendly and open, surprised only by the fact that the photographer was traveling alone. The most difficult part of the project was knowing when to finish it. Frankfurter said in many ways working on a project is like being in a relationship.

“In the beginning you’re infatuated, and that’s the only thing on your mind. I felt like that was reality and everything I did in between was waiting to get back down there; it took over my life for a while, and I felt I could keep going and go deeper.”

“It was more important I publish it as a complete body of work than to keep feeding my need to keep going back over and over again,” she added. In 2014, FotoEvidence published the work as a book. The work was recently on view at Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon.

As for Trump’s idea of building the wall, Frankfurter said his vision of Mexico is a far cry from what she has experienced.

“I never imagined we would get to where we are now. The fact this is happening seems farcical to me in so many ways. … There’s part of me that is just numb and wearied by it; there’s nothing I could ever do or say or show to this particular demographic that is going to change their minds. So I have to find different ways of channeling my energy other than getting crazy by it.”

Michelle Frankfurter

Michelle Frankfurter

Michelle Frankfurter

Michelle Frankfurter