It would be an understatement to say that the politicians who run the city of Chicago released the video of Laquan McDonald’s death with extreme reluctance. Mayor Rahm Emanuel opposed the release for the better part of a year, and went so far as to take on a journalist in court over a Freedom of Information Act request that sought to make the video public. When a judge ruled against the city in that case last week, it was widely expected that Emanuel would push for an appeal. Instead, he announced that the city would end its fight and finally release the footage.

The decision was accompanied by comments from Emanuel that many in Chicago would have welcomed months earlier: The police officer who shot McDonald 16 times had committed a “hideous” act, Emanuel said during a Nov. 23 conference call with local leaders, and it was clear from the video that he had taken “the law into [his] own hands.”

“What happened here is wrong,” Emanuel said, according to the Chicago Tribune. Later that same day, news broke that Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez would be charging the officer, Jason Van Dyke, with first-degree murder.

This rapid turn of events—the city had gone from being all but silent on McDonald’s death to condemning the officer who caused it—was widely interpreted as the result of political calculation. Emanuel seemed to have realized that the pressure on him to release the video was too strong to continue resisting. Alvarez, who is facing a tough re-election bid next year, acknowledged that she moved up her announcement of the charges against Van Dyke due to the video’s imminent release, fearing, perhaps, what might happen if the awful footage preceded any consequences for the officer. Meanwhile, Chicago Police Chief Garry McCarthy, whose ouster a group of black city aldermen have been calling for, took the opportunity afforded to him by all the commotion over the McDonald case to quietly do something activists have demanded for years: He moved to fire Dante Servin, a police officer responsible for yet another controversial shooting, of Rekia Boyd, from 2012.

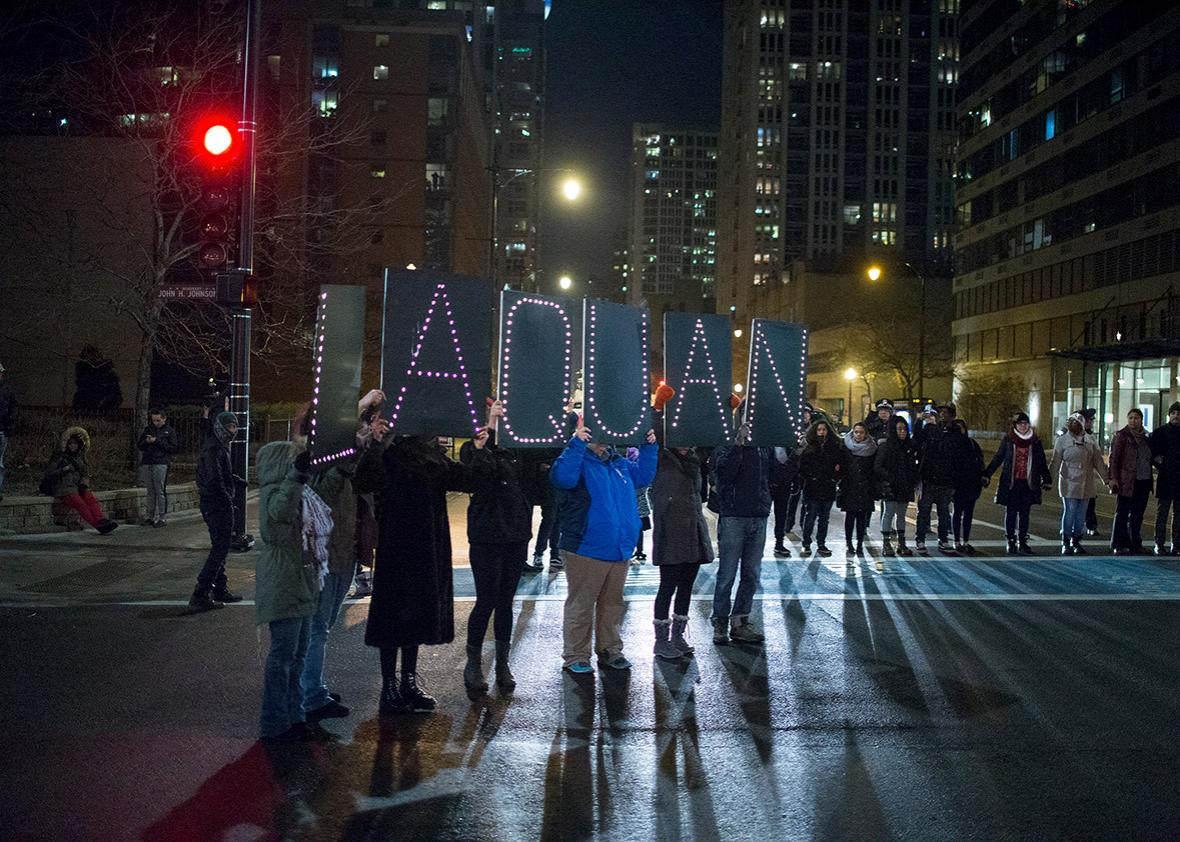

Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

The repercussions for both officers, in other words, seem less the result of the criminal justice system working as it should, and more the product of politically motivated decision-making brought on by the court-mandated release of the McDonald footage. There’s something intuitively enraging about that motivation—why can’t our elected representatives do the right thing just because it’s right? But, viewed another way, there’s also something reassuring and exciting about it. Often, change happens not when the people in power have a moral or ethical epiphany, but when their constituents force them to make decisions that they might not otherwise make. Even under the most cynical reading of what happened in Chicago this week, officials were responding to the threat of a public backlash. That means the efforts of those invested in justice for Laquan McDonald and Rekia Boyd worked. It means the climate has changed to the point where powerful politicians know that—under some circumstances, at least—brushing the killing of citizens by police under the rug is no longer a viable option.

The Black Lives Matter movement caught fire after prosecutors in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, failed to win indictments of cops who took the lives of citizens. The perception among those outraged at the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner was that the prosecutors had soft-pedaled their cases because protecting their working relationships with the police was more important than satisfying constituents who wanted to see the officers charged.

Prosecutors dealing with cases of police violence no longer seem so assured that they can stand by police without repercussions. As research by Bowling Green University criminologist Philip Stinson shows, the number of police officers who have been charged with manslaughter or murder for shooting civilians this year—Van Dyke is the 15th—is much higher than it’s been at any time during the past decade: Between 2005 and 2014, the United States saw an average of just five officers per year facing such charges.

This isn’t to say that we want our prosecutors to be making their decisions based on public opinion alone—mob justice is no kind of justice either. But the events in Chicago this week suggest that, when it comes to holding police accountable for violent misconduct, elected officials are feeling the ground shift beneath them. For advocates of reform who want to see it become unacceptable for police officers to get away with murder, that should feel like a victory.