With the death of Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia earlier this month, the big union-busting case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, is also likely DOA—just in time for California’s other portentous education lawsuit to take center stage.

Vergara v. California, the controversial lawsuit over teacher tenure in California public schools, is back in court after two years. When the suit was first filed in 2012, Vergara’s plaintiffs—nine public school students represented by Students Matter, a reform group financed by Silicon Valley entrepreneur David Welch—argued that their educations had suffered at the hands of the disproportionate number of ineffective teachers at their schools.

The lawsuit maintains that the state has a constitutional obligation to provide California kids with a high-quality education, but the lightning-fast tenure process deprives them of that right: Teachers get evaluated for tenure in the spring of their second year on the job, in some cases before they’re even fully credentialed, and once tenure’s in the bag, the process of firing them is protracted and expensive and beyond the resources of most districts.

Overturn tenure, Vergara’s argument goes, and you’ll go a long way toward leveling the playing field for California students. At the moment, seniority is the major determinant of a teacher’s status; California’s “last-in, first-out” (or LIFO) firing formula doesn’t factor in teacher effectiveness during layoffs: All that matters is when you showed up for work the first time.

Responding to the suit, the unions and the state of California argued that tenure created a more stable workforce, that more experienced teachers also tended to be more skilled ones, and that there was no proof that poorer schools got stuck with worse instructors as a result of tenure laws.

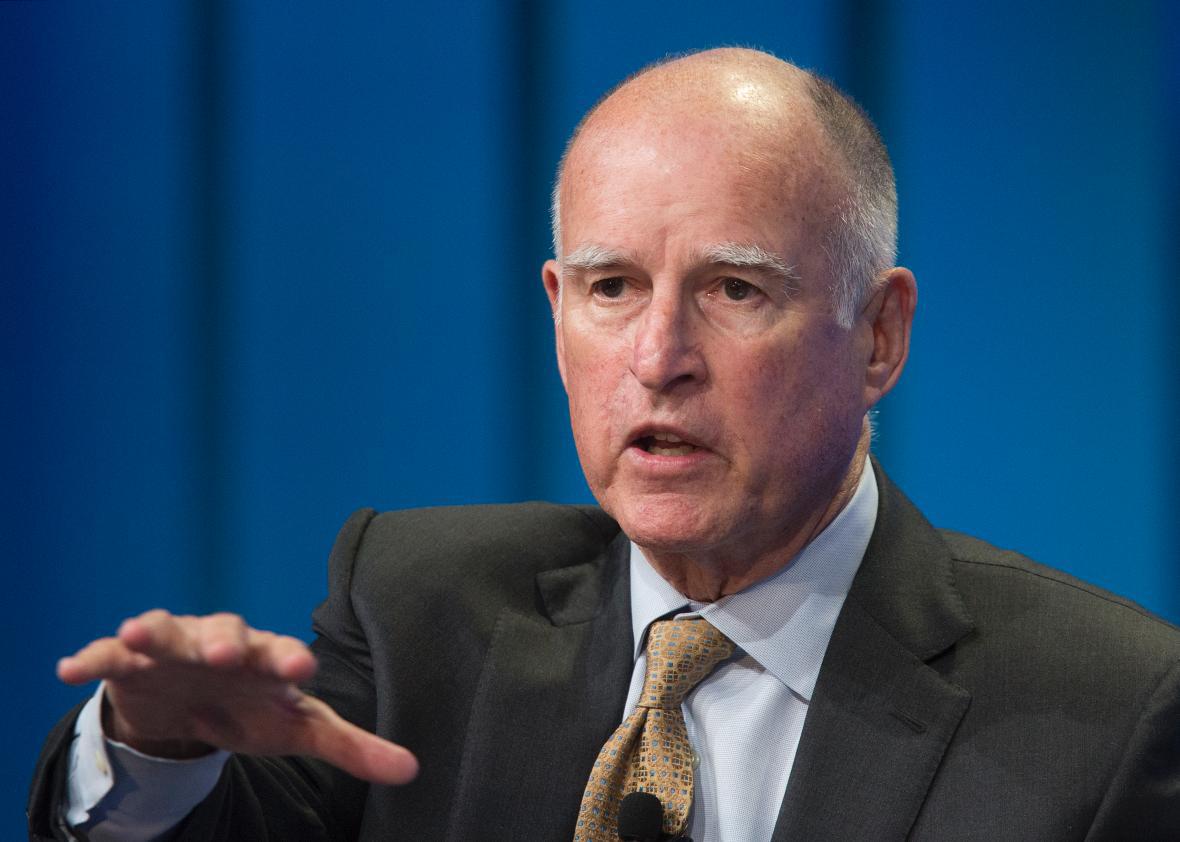

In 2014, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Rolf Treu found on behalf of the Vergara plaintiffs and overturned the laws; the evidence presented at trial, he famously wrote, “shocks the conscience.” But nothing concrete actually changed while the case continued to make its way through the system. Oral arguments in the appeal, which was backed by teachers unions and California Gov. Jerry Brown, began Thursday.

So what’s going to happen—besides a likely appeal to the state’s Supreme Court—and what should happen?

As the saying goes, an astronaut could see from space the flaws in how California hires and fires teachers. Granting tenure after only three semesters on the job—ridiculous. Laying off teachers based solely on seniority—not so brill. But are the problems highlighted by the Vergara plaintiffs ultimately a distraction from the larger issues facing American schools, particularly those in urban districts?

As Richard Kahlenberg persuasively argued in a 2014 Slate piece about the original Vergara decision, the fight over teacher tenure is something of a red herring if you believe, as I tend to, that the real scourge of public schools isn’t bad teaching, but poverty and (re)segregation, which was the subject of a powerful New York Times op-ed published earlier this week.

As Kahlenberg wrote, “The big problem in education is not that unions have won too many benefits and supports for teachers. It’s the disappearance of the American common school, which once educated rich and poor side by side.” In this narrative, bad teachers proliferate at high-poverty schools not just because they’re impossible to fire, but because the better teachers don’t want to teach at those schools. As Lily Eskelsen Garcia, the president of the National Education Association, said in a statement on Wednesday, “High-poverty districts do not suffer from too few teachers being removed; they suffer from too much teacher turnover.” Numerous studies have shown that, with or without tenure, teacher attrition is much higher at schools with high concentrations of poor students because those schools have more stressful working conditions than their middle-class counterparts.

Nick Melvoin taught at one of those high-poverty schools in Watts, Los Angeles—until he was laid off, two years in a row, a victim of LIFO. Melvoin, who is now a teacher organizer with Teach Plus and a recently declared candidate for the L.A. Unified school board, testified on behalf of the plaintiffs in Vergara and thinks that overturning the statutes contested in Vergara “would be a game changer. It’s necessary but not sufficient,” he said. “It’s obviously not a silver bullet—I don’t think those exist in most policy areas, including education—but I think it would change how we’re able to ensure that all kids get taught by effective educators.”

That is, until the next lawsuit.