On May 15, 2015, just a few months before the U.S. and other world powers signed a nuclear deal with Iran, President Barack Obama convened what was to be a high-profile meeting of Middle East leaders at Camp David. King Salman of Saudi Arabia, however, was a no-show. King Hamad of Bahrain elected to go to a horse show in the U.K. instead. The elderly rulers of Oman and the UAE also stayed home, citing health concerns. This was widely seen as a snub by leaders deeply angered by the soon-to-be-signed nuclear deal and an overall sense that the Obama administration was shifting politically toward Tehran.

Obama, understanding that he needed—if not these leaders’ support—at least their reluctant acceptance, had to do something lest he risk the No. 1 priority of his foreign policy agenda. So he promised to expedite arms transfers to the region and improve intelligence sharing, all in the name of fighting both terrorism and Iran’s growing influence. Then, a few months after the Iran deal was signed, Saudi Arabia and the U.S. inked a $1 billion arms deal meant in part to assuage Saudi concerns about Iran. King Salman was reportedly “satisfied with these assurances,” and the weapons were quickly turned on Saudi Arabia’s southern neighbor, Yemen, where the kingdom and its Gulf allies were fighting an increasingly brutal war against the Houthi rebels they viewed as Iranian proxies.

For the next year, the U.S. provided logistical support to the Saudi effort in Yemen, despite the Obama administration’s very public concerns about the large number of civilian casualties, the unclear degree to which the Iranians were really behind the Houthis, and the possibility that the chaos caused by the war was helping al-Qaida. Obama finally took some steps to back away from the controversial war in December 2016, but by that point the damage was done: More than 7,000 people had been killed, Yemen was on the brink of catastrophic famine and the world’s worst cholera outbreak, and a new U.S. administration was on its way, arriving with none of the Obama team’s qualms.

No one ever explicitly stated that the Obama team’s support for a war it clearly thought was a bad idea had something to do with the Iran deal, but it was widely read that way at the time. Before the deal was struck, Rep. Adam Schiff told Face the Nation’s Bob Schieffer, “it’s vitally important that we have the Saudis’ back in what they’re doing in Yemen right now, because that may give the Saudis some comfort that, even if we do reach an agreement with Iran on its nuclear program, that doesn’t mean that we’re not going to be willing to confront Iran as it tries to expand its quite nefarious influence throughout the region.” (Last year, Schiff was among the overwhelming majority of House Democrats who voted for a resolution expressing concern about the humanitarian and strategic consequences of the Yemeni Civil War.) Sen. Chris Murphy recently told the New Yorker, “The Obama Administration was legitimately worried that a major fissure between the United States and Saudi Arabia could weaken the Iran deal. … I think these arms sales were a way to placate the Saudis.”

At the time, turning a blind eye to what Saudi Arabia and its allies were up to in Yemen might have seemed like a reasonable compromise in order to win Salman’s grudging acquiescence. A regrettable but necessary sacrifice, given what was at stake—keeping a weapon of mass destruction out of Iran’s hands. Looking today at the emaciated bodies of children lying in the 45 percent of Yemeni hospitals still operating—the others having been closed due to lack of funds or deliberately targeted airstrikes—it seems less clear that the trade-off was worth it.

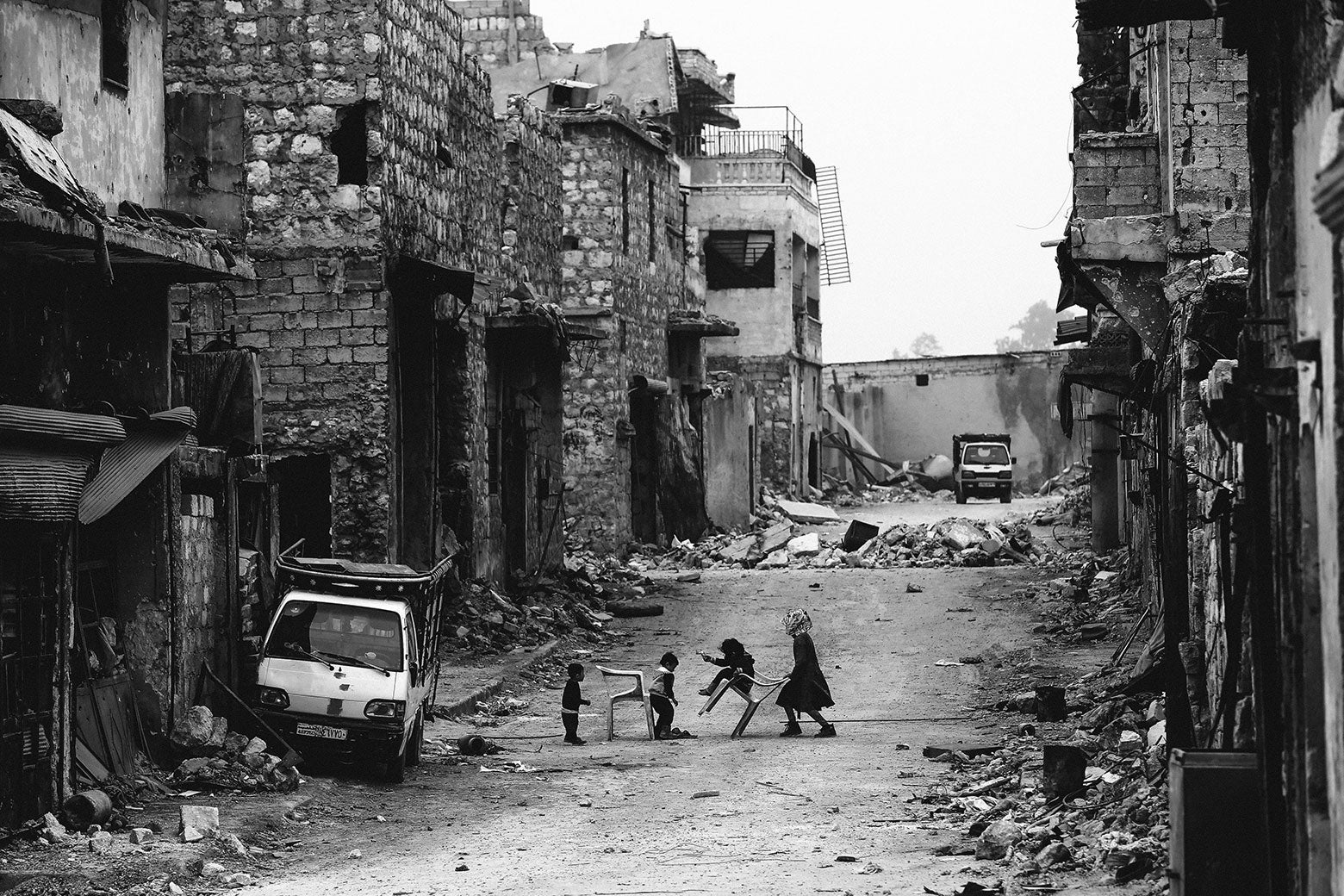

And it’s not just Yemen. Since 2015, the Middle East’s sectarian conflicts have only become deeper, more violent, and more intractable. From the half-million people killed in Syria to the rise of ISIS to the massive refugee crisis that has strained the world’s humanitarian capacity to its breaking point and contributed to the rise of right-wing populists in the West, it’s much harder now to say that Obama made the right decision in prioritizing the Iran deal above all else. The concessions the U.S. had to make in order to get the agreement were judged at the time as necessary to prevent the worst-case scenario—an Iranian nuclear weapon. But what if what’s happened since is the worst-case scenario?

Judged only on its explicitly declared goals, the Iran deal is working. In the two and a half years since the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was signed, Iran has not acquired a nuclear weapon and, according to both U.S. and international assessments, has mostly complied with the measures meant to prevent it from doing so. The common complaints about the deal—that it includes a sunset provision, that it involved returning funds to Iran that were frozen after the Iranian revolution, that it did not address Iran’s ballistic missile program or support for foreign militias—seem predicated on the dubious notion that Iran would ever have agreed to a deal in which it got nothing in return, and remain unpersuasive.

The deal’s most vocal critic, Donald Trump, seems opposed to it in large part because it was Obama’s signature foreign policy achievement. And the fight in the U.S. over whether to preserve the deal—which Trump called “the worst deal ever” on the campaign trail and “terrible” in his State of the Union, but recertified just a few weeks ago—has become something of a proxy battle over the Obama administration’s foreign policy legacy. But if the attacks on the JCPOA itself don’t hold water, the deal’s defenders should also acknowledge that its larger impact has been more mixed than we like to admit.

Obama always made clear that an agreement on nuclear weapons wouldn’t necessarily change Iran’s larger pattern of behavior or that of its rivals. “If they don’t change at all, we’re still better off having the deal,” he argued. Still, he suggested that the diplomatic opening provided by the deal could change the dynamics of the region. “It would be profoundly in the interest of citizens throughout the region if Sunnis and Shias weren’t intent on killing each other,” he told the New Yorker’s David Remnick in 2014. “And although it would not solve the entire problem, if we were able to get Iran to operate in a responsible fashion—not funding terrorist organizations, not trying to stir up sectarian discontent in other countries, and not developing a nuclear weapon—you could see an equilibrium developing between Sunni, or predominantly Sunni, Gulf states and Iran in which there’s competition, perhaps suspicion, but not an active or proxy warfare.”

This is not what happened on either side of the Middle East’s sectarian divide. Instead, the deal has more often contributed to escalating tensions. In retrospect, this was foreseeable: Iran was perfectly capable of projecting power across the region with or without a nuclear arsenal. As for its rivals, they never trusted Iran’s assurances and saw warming relations between Tehran and Washington as a new and potentially even greater threat.

Following the nuclear deal, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf monarchies, with aid from the U.S., stepped up their involvement in the tragic and destructive war in Yemen to counter perceived Iranian encroachment in their backyard. The Saudis also exacerbated the region’s sectarian tensions by executing a prominent Shiite cleric in January 2016. This, predictably, led to the ransacking of the Saudi embassy in Tehran and the cutting off of diplomatic relations between the two countries. The Saudi moves were viewed as a reaction to warming U.S. ties with Iran. As political scientist and Mideast analyst Marc Lynch wrote, “Saudi Arabia views Iran’s reintegration into the international order and its evolving relationship with Washington as a profound threat to its own regional position. Mobilizing anti-Shiite sectarianism is a familiar move in its effort to sustain Iranian containment and isolation.”

At the same time, rather than moderating its regional ambitions as the JCPOA’s proponents might have hoped, Iran has spent the years since the deal was signed supporting a network of Shiite militias in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and other countries, part of a larger project to, as BuzzFeed’s Borzou Daragahi put it, “establish territorial dominance from the Gulf of Aden to the shores of the Mediterranean.” Iran might have done all this regardless. But it was also responding to the Saudi actions. Either way, there’s certainly no evidence that nuclear diplomacy, or the lack of a nuclear weapon, has helped the neighbors overcome their differences.

While the Obama administration kept its public expectations low, the president also suggested it was possible the deal might impact Iranian domestic politics by empowering moderates within the ruling regime. After all, moderate President Hassan Rouhani was elected on the premise that through improved relations with the West, he could deliver economic growth to Iran. Rouhani got his nuclear deal and won re-election last year, but it’s hard to say that his faction has been “empowered” beyond that. In the months following the deal, the conservative hard-liners who had opposed it stepped up arrests of political opponents in what was seen as a bid to re-establish their position. Human Rights Watch noted that “Iranian dual nationals and citizens returning from abroad were at particular risk of arrest by intelligence authorities, accused of being ‘Western agents.’ ” Iran led the world in executions per capita in 2016 and global democracy monitor Freedom House stated last year that there was no indication that Rouhani’s moderates were “willing or able to push back against repressive forces and deliver the greater social freedoms he had promised.”

The protests that swept the country in January, sparked by economic grievances, suggest that most Iranians have not benefited from the lifting of sanctions, and the thousands of arrests and dozens killed in those protests certainly don’t indicate that Iranian security forces have become any more tolerant of dissent. The more recent acts of defiance by women protesting the country’s mandatory hijab rules may be another sign that Iranians are tired of waiting for the regime to reform at its own pace—and that the deal did not motivate the change they so desperately desire.

Any consideration of Obama’s priorities in the Middle East has to address the most contested part of his legacy, the still unfolding crisis in Syria. Many critics, including former members of his administration, have charged that Obama’s reluctance to intervene to a greater extent in Syria was motivated in part by the desire to achieve the nuclear agreement with Bashar al-Assad’s patron, Iran. In the new documentary, The Final Year, which follows Obama’s foreign policy team throughout 2016, adviser Ben Rhodes essentially legitimizes this claim by defending Obama’s hands-off policy in part by saying that if the U.S. had intervened more forcefully in Syria, it would have dominated Obama’s second term and the JCPOA would have been impossible to achieve. Rhodes may be right, but it’s less and less clear as time goes on that this was the right trade-off. Looking at the devastating consequences of the Syrian war, not just for that country but for the region and the world, it’s hard not to argue that Obama should have made Syria his main and overwhelming foreign policy focus, to the exclusion of nearly everything else, Iran deal be damned.

Obama and his officials have consistently argued that there was nothing they could have done to stop the carnage in Syria: There were legitimate questions about whether the Saudi-backed anti-Assad rebels were reliable partners; the U.S. track record on arming rebels is dismal; U.S.-backed regime change has been a disaster in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya. There were, as Obama and his defenders correctly stated time and again, “no good options” for Syria. The problem is, as time went on and the conflict continued to worsen, the options only got fewer and worse.

What seems likeliest is that a president who was elected promising to end the Bush administration’s wars was wary of yet another costly quagmire in the Middle East. But the Trump administration’s limited airstrikes on Assad’s air force last April in response to a chemical weapons attack—an action the previous administration famously did not take in a similar situation—has not sucked the U.S. into a larger unwanted war against Syrian forces or led to an accidental clash between the U.S. and Russia, as Obama defenders would have predicted. (The U.S. is keeping troops in Syria, as the Trump administration recently announced, but so far they have not engaged directly with Assad’s military.) In other words, not every military action is a slippery slope leading to a new Vietnam or Iraq.

Unfortunately, Trump’s willingness to use force was coupled with a lack of any larger strategy for Syria and a disinterest in diplomatic engagement. Could Obama’s team, using a combination of military power and active diplomacy, have done better, particularly early in the conflict when there might have been more room for compromise?

Perhaps it’s naïve to think so. Iran and Russia never seemed interested in putting real pressure on Assad—and were willing to spend whatever it took, in money and lives, to keep him in power—while the opposition was unlikely to agree to any settlement that let him stay. But Obama loyalists who say the situation was hopeless underestimate an administration that, against long odds and widespread skepticism, achieved the Paris climate agreement, the diplomatic opening with Cuba, and of course, the Iran nuclear deal.

Just weeks before the final deal was reached, the JCPOA also looked hopeless, with deadlines blown and major differences remaining between the parties. At home, Obama was up against a U.S. Congress so opposed to the deal that it invited the prime minister of Israel to give a major address denouncing it. The administration had to do a constitutionally questionable end-run around Congress just to have any hope of making the deal happen. And yet, it did, in no small part because of the importance the administration attached to it. Could a similar commitment have stopped the killing in Syria? We’ll never know, but it is probably true that Obama and his team couldn’t have done both.

I fully supported the Iran deal, and the trade-offs involved, in 2015. In the face of sustained attack from the current administration, I have consistently defended it. But just because the deal was struck for the best of reasons, and just because Trump is against it, doesn’t mean it shouldn’t face retroactive scrutiny. An honest account of the consequences of the deal, and the assumptions that led to it, is necessary if we are to have better policies going forward.

No country in the Middle East should have nuclear weapons. No country in the world should have nuclear weapons. The risks are far too high, and the slow and steady work of nonproliferation must continue. Without downplaying the risks in any way, it’s still fair to say that if Iran acquired a nuclear weapon, it probably wouldn’t use it, just as other nuclear powers have not. It’s a very real, but theoretical, danger. Nuclear weapons have done far less damage in the last 70 years than the wars in Syria and Yemen have in just the last two. Placing nuclear nonproliferation above all else is not always the right call and may have been motivated by an overly fatalistic view of the region.

Americans, both leaders and citizens, often think of the Middle East’s sectarian divides as permanent, “rooted in conflicts that date back millennia,” as Obama once put it. If such conflict is actually eternal and inevitable, then taking the deadliest weapons off the battlefield is indeed the best outcome that outsiders can hope for.

But a recent book of essays, Sectarianization, edited by political scientists Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel, convincingly argues that sectarian conflict is a “process shaped by political actors operating within specific contexts pursuing political goals that involve popular mobilization around particular (religious) identity markers.” In other words, sectarian identity—Shia or Sunni—is something that powerful countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia use to project influence and undermine each other. The people of the Middle East, according to this analysis, aren’t simply fated to continue killing each other over ancient grievances forever. Their conflicts are rooted in modern power politics, and the combatants respond to provocations and incentives.

Sectarianization is arguably what drives most of the Middle East’s violence today, and rather than countering it, the Iran nuclear deal more often appears to have accelerated it, as rival powers pushed for dominance, sometimes with the acquiescence of a U.S. government laser-focused on the nuclear issue. In order to address a terrifying but hypothetical danger—an Iranian nuke—the Obama administration’s foreign policy accepted a real and catastrophic one.

One could still argue that it was worth it. A world with no nuclear deal could have led to two bleak scenarios: one in which the U.S., Israel, or Saudi Arabia attempted to destroy Iran’s nuclear program by force; another in which Iran successfully acquired a nuclear weapon, possibly prompting the Saudis and other Arab leaders to try to acquire their own. The current standoff with North Korea certainly doesn’t make this scenario seem very appealing. But the North Korea analogy can be viewed another way: Right now, despite Trump’s bluster, the U.S. and its allies are holding off on attacking Kim Jong-un’s nuclear program, more or less accepting the fact that North Korea is a nuclear power now, for fear of igniting a catastrophic regional war. In the Middle East, by contrast, Iran doesn’t have a nuclear weapon but the catastrophic wars, with hundreds of thousands dead, are happening in Syria and Yemen anyway.

This is not an argument that Trump should finally kill off the deal, which he recently suggested he would do in May unless European allies rewrite the agreement to address his objections. Given that Iran is, by all accounts, abiding by the agreement, this would accomplish little except winning international sympathy for Iran, giving it a green light to resume its nuclear program, and further underlining to America’s foes and friends that our agreements aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on. Plus, ending the deal now would do nothing to counteract sectarianization, given that the current administration’s Iran strategy often seems motivated by complete and uncritical backing of the Sunni states and Israel and co-signing those countries’ views of Iran.

One aspect of Obama’s view of the Middle East was completely correct: The United States gains little, and probably makes things worse, by taking sides in sectarian grudge matches. Its engagement with Iran after decades of tension was an admirable attempt to take a more balanced approach to Mideast diplomacy, but its effect was to do the opposite. Elected in part on a promise to extract the U.S. from the conflicts of the region, Obama ended his term with America just as enmeshed in them as ever.

The current administration is probably a lost cause, but if a future president wants to take productive lessons from the Obama era, it’s that we should give up on the idea that we can pivot away from the Middle East or that one deal—even a deal to prevent an aggressive power from acquiring a nuclear weapon—should take precedence over all other issues. Sustained diplomatic engagement to help actors in the region toward productive settlements in places like Syria, Iraq, and Yemen—and I haven’t even gotten into Israel and Palestine—will take a long time and be marked by much more frustration than triumph under even the best circumstances. In other words, it will make the Iran deal look easy.