In 2013, an app called Lulu briefly became the object of the internet’s fascination and scorn. The app’s purpose was to allow women to rate men, Yelp-style, and I had mostly forgotten all about it, writing it off as just another problematic app in a world full of them. My memory was jogged, however, by the news that the political-data firm Cambridge Analytica may have harvested as many as 50 million user profiles by inappropriately using information extracted from Facebook through a personality app. I wasn’t one of the nearly 300,000 users who had enabled that app, but I easily could have been one of the users whose data was hoovered up as a result of its advent. So I went to the Facebook page that lists the apps that have permission to stalk my profile, and sitting there I discovered my own personal blast from the past: Lulu.

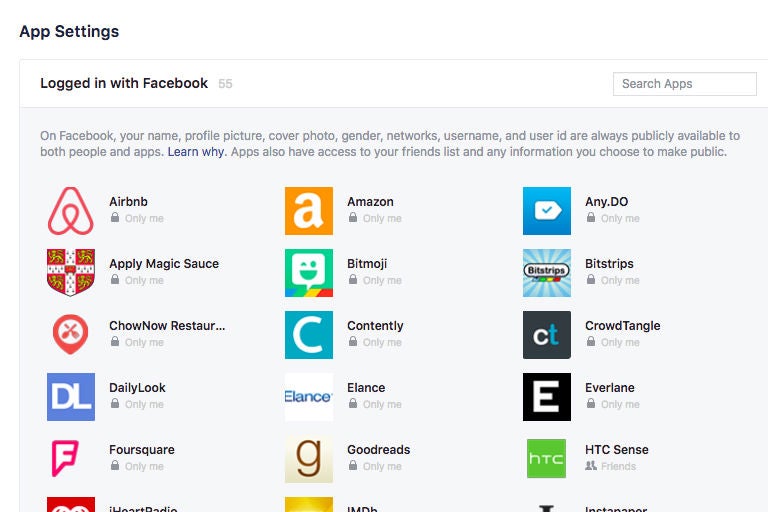

While I hadn’t thought about Lulu in years, all along it’s been allowed access to my profile, friend list, birthday, photos, and more. The app was sold to Badoo in 2016 and seems to be defunct now, which is probably for the best. But it’s just one of the dozens of apps I’ve given permission to access my Facebook data over the years. And the list of them is quite a walkabout the past few years of the social web: There are some recognizable names in there, like Airbnb and Spotify, both of which required users to sign up through Facebook when I first got them. I also spy Words With Friends and various knock-offs, Draw Something, a quiz that tells you which Lost character you are (I’m a Hurley), and the app for the long-dead News Corp iPad-native newspaper, the Daily. Lulu might not even be the most embarrassing one—when did I give Facebook access to Kim Kardashian: Hollywood? I think of myself as fairly conscientious about these things—I’ve definitely gone in and disabled an app or two over the years—and yet my list is just as cluttered as anyone’s, full of apps I never use and certainly wouldn’t want to have access to the full or even partial dossier of what Facebook knows about me.

What previously might have looked like a case of bad digital hygiene now seems like potentially something much worse, thanks to what’s come to light about Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook. The firm, which worked on the Trump presidential campaign in 2016, paid 270,000 users to participate in a 2014 personality survey to help the firm build psychological profiles. Those who signed up also gave permission for the app to scrape some of their data, and due to Facebook’s rules at the time, apps were permitted to scrape not only information from users who signed up but also the information of their friends on the social network, which is how the number ballooned from something in the hundreds of thousands into the tens of millions.

You can see how this would have a person reconsidering every app she ever gave permission to access her Facebook data. If Lulu was craven enough to release an app that was all about superficially rating men, who knows what nefarious stuff it was doing on the down-low? Not to mention some of the apps I enabled back in the day that make Lulu look fastidious and well-thought-out in comparison. Anyone remember whatwouldisay? It was a bot designed to create Facebook statuses based on your past updates, and I must have enabled it in 2013, because that was the year of its short-lived heyday. It was designed by a team of six graduate students at a Princeton Hackathon weekend, and I’m guessing they didn’t put much effort into permissions at the time. Does that mean that, if, say, one of those six kids was running low on cash now or in the future, he or she could sell my profile data for a quick buck? Maybe! I have a bunch more similarly weird apps enabled—Zaarly? Playster?—and though I could disable them all now, what would that mean for the information they already have on me? Does it even matter, since apparently Facebook rules used to allow the apps people I was friends with were using to give up data on me, regardless of whether I gave permission? And what lesson should any of us take from this, other than we should be mindful of who can access our data and for how long, and/or that we might all be better off absconding to caves?

When I signed up to play a new game or to try a new startup service back in the halcyon days of Facebook being a not-scary place, I thought at worst I was subjecting myself to some spam, the digital equivalent of a few years of Pottery Barn catalogs. What many of us realized too late is that when the data operation is large and potentially leaky as Facebook’s is, this information has applications beyond selling throw pillows. It might be used to elect a president.