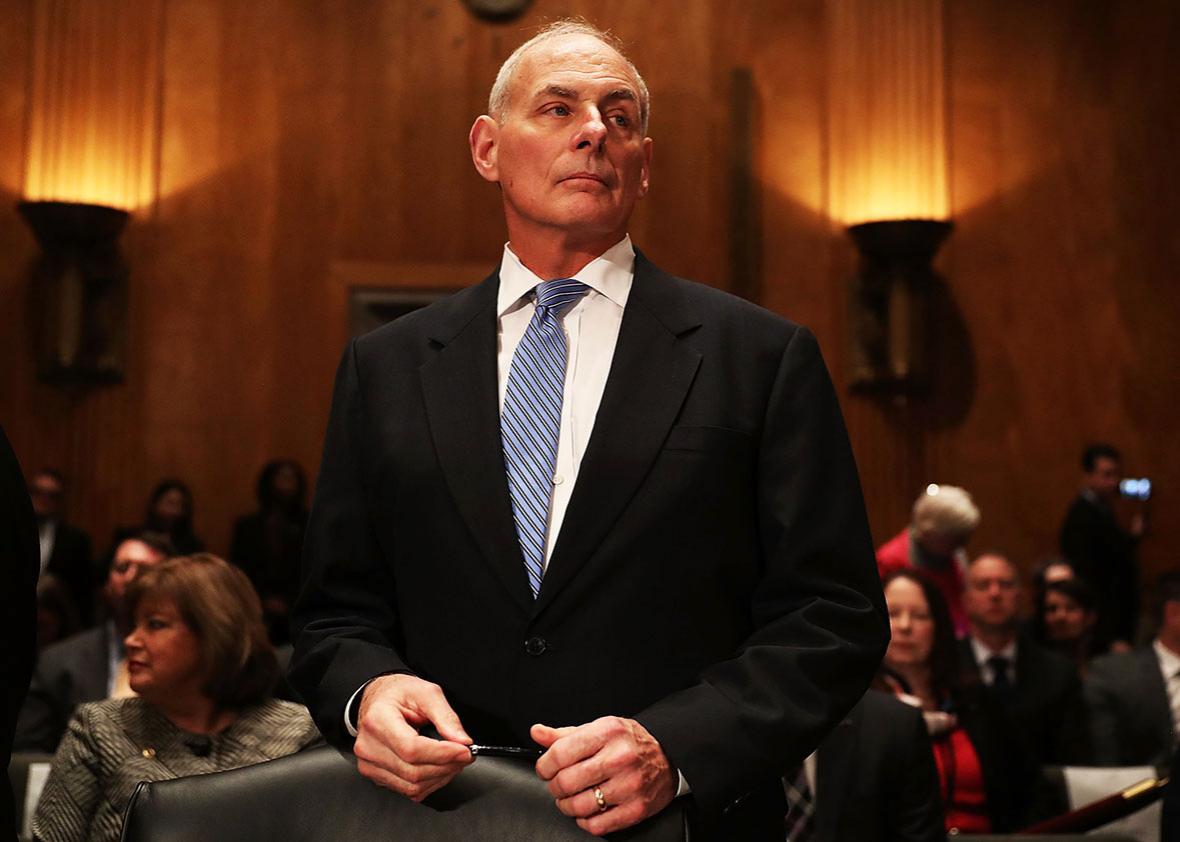

Gen. John Kelly faced almost nothing but softballs in his confirmation hearing Tuesday afternoon to be secretary of homeland security.

From all accounts, he does seem singularly qualified for the job: a retired four-star Marine general who, in his last post, was head of U.S. Southern Command, which handles some of the same issues as the department he will soon lead, including counterterrorism, counternarcotics, and border security. Former Defense Secretary Robert Gates, to whom Kelly served as senior military adviser, introduced him to the Senate Homeland Security Committee as “a man of great moral authority” that he’d trust with his life.

In more than two hours of hearings, Kelly made a point of saying he has no problem “speaking truth to power” and then took several positions that run contrary to those of the man who nominated him for the post.

Asked what he thought about the idea of building a wall on the Mexican border, Kelly said he knows, “as a military person,” that “physical defenses in themselves would not do the job.” He added, “I believe the defense of the Southwest border starts 1,500 miles to the south, with Peru, which is very active in going after drug traffic.” He added that “working with partners overseas” is one of the most useful things we can do to improve our security. He also said the best way to halt drug traffic is to “halt the demand.”

Sen. John McCain, a vocal critic of torture, having endured it as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam, asked Kelly what he thought about abiding by the Geneva Convention outlawing the practice. Kelly replied, “I don’t think we should ever come close to crossing [that] line.”

Democratic Sen. Claire McCaskill asked to what degree Kelly accepted the conclusions of the intelligence community’s report on Russia’s hacking of the 2016 election, especially the finding that Vladimir Putin sought to damage Hillary Clinton and boost Donald Trump’s chances of victory. Kelly replied, “With high confidence.”

Asked why people from southern countries try to cross the American border, Kelly—who, as head of Southern Command, spoke often of the need to foster economic development in Central and South America—replied, “They, most of the time, don’t come here for any other purpose except to have economic opportunity and to escape violence.” He said nothing about Trump’s claim, during the election campaign, that they come here to rape and murder American citizens.

Sen. Gary Peters, Democrat from Michigan, noted the “great deal of fear” among Muslim Americans in his state and asked about the idea—another of Trump’s proposals—of putting mosques under continuous surveillance and establishing Muslim databases. Kelly said, “I don’t think it’s ever appropriate” to do those things. Peters asked him whether the World War II–era internment of Japanese citizens provides a valid precedent for Muslim roundups, as Trump has suggested. Kelly replied that it doesn’t, though he added that he is not a lawyer. He said he “looks forward” to the work of gaining Muslim Americans’ trust in rooting out extremists.

Kelly came under something close to grilling from California’s Democratic Sen. Kamala Harris (and that state’s former attorney general), on whether he plans to deport children of illegal immigrants who have spent their entire lives in America. Kelly replied cautiously, noting that he will be required to enforce the law. Noting that he would have limited law-enforcement resources, Harris asked how high this activity would rank in his list of priorities. He replied, in a tone more hesitant than usual, that “law-abiding individuals” of this sort “would not be at the top of the list.”

To Sen. Rand Paul’s questions about blanket surveillance and wholesale data collection, Kelly said he favored “the traditional route” of directed search warrants. On detaining illegal immigrants without prior trial, he replied, “I’m pretty committed to the Constitution.”

Kelly received no questions about any of his more controversial positions—his opposition to transferring detainees at Guantánamo Bay to high-security prisons in the United States (even though more than 300 violent terrorists are currently in those prisons), his warnings of terrorists coming into the country from the Southern borders (with no evidence), and his estimate that more than 100,000 people in the Western Hemisphere may have died as a result of terrorism since 9/11 (when official estimates put the number at roughly 1,000).

A few senators warned him that he faced an almost absurdly tough job, though he seemed to know that already. In his opening statement, Kelly said he has experience at managing large, multimission organizations, but the Department of Homeland Security is almost a parody of the concept. It was created in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks as a way to consolidate all the federal agencies (aside from the Department of Defense) that play any role in protecting the country. Yet the result has been a ramshackle bureaucracy with fractured authority and little clout. One senator cited a recent report by the Government Accountability Office, concluding that of 22 DHS acquisition programs, only two are on track—as well as an inspector general’s report that, in its 13 years of existence, DHS still doesn’t have a viable human resources office.