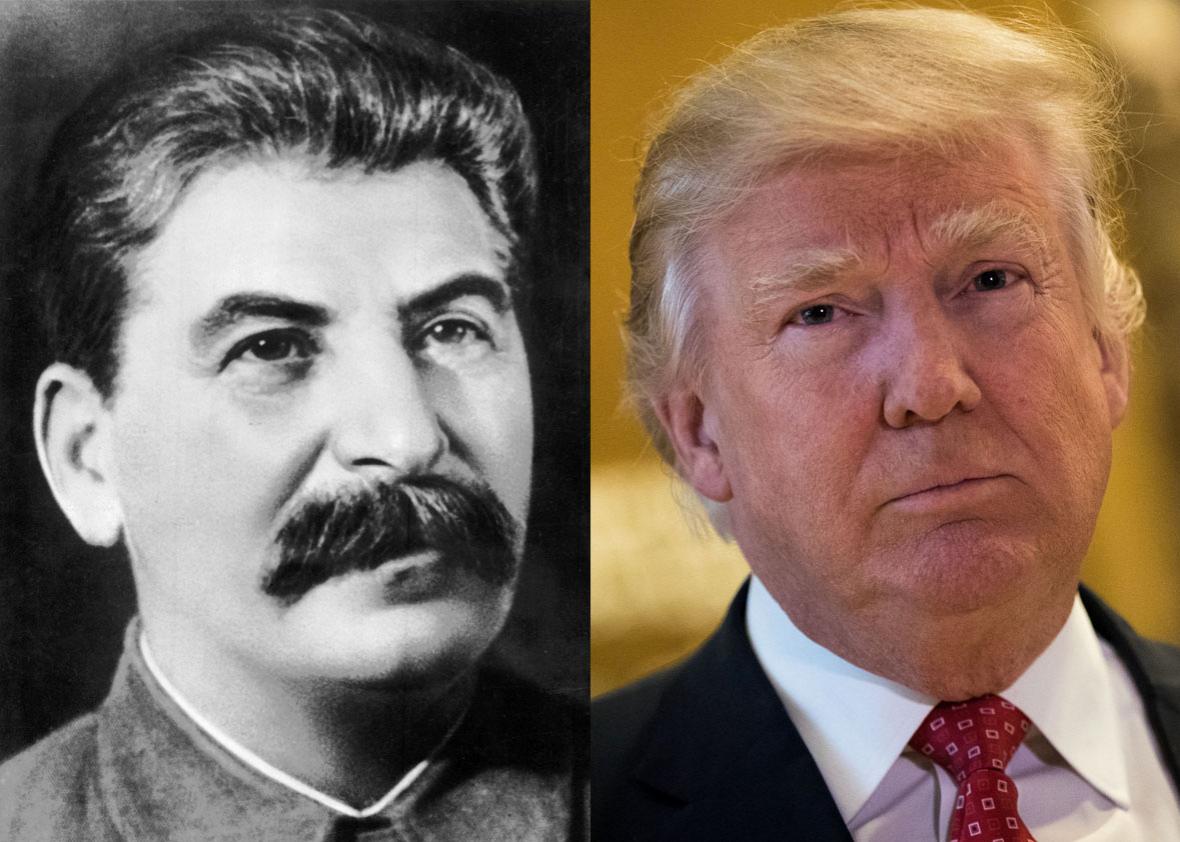

Donald Trump shares several important traits with his ally Vladimir Putin—foremost among them, the deployment of outrageous lies as a political tool. Putin is a master of disinformation. After Russian troops and aircraft invaded Ukraine in 2014, for example, he simply denied they were there, which slowed and destabilized Western response. The deployment of falsehood by Putin’s regime is right out of the old Soviet playbook. It was, in particular, a specialty of Josef Stalin’s, who projected a similar strongman image and whose constant flood of lies was central to Communist rule for decades.

Trump comes by his carnival-barker falsehoods through a different lineage, via the red-blooded capitalist traditions of the American salesman. But it’s worth giving a comparative look at the effectiveness of a regime of lies in Stalin’s Russia, especially given the surprising penetration of Russian interests in our incoming American regime.

Of course, it is hyperbolic to compare Trump’s lies to Stalin’s. The differences between the two figures are many. (For one thing, Stalin actually read his intelligence briefings.) Trump and some of his Cabinet appointees are dazzled, even seduced, by the Russians, but their interest is clearly more in the culture of the current oligarchs than the drab, murderous Soviet functionaries who trained Putin and his ilk. Nonetheless, it’s worth following just one strand of comparison between these self-declared strongmen: the use of lies as a principle of control. As we struggle through the muck of ludicrous but toxic disinformation that currently infests our political swamp, we should look to the past to remind ourselves of both the potency of rampant political dishonesty at the highest levels of government and the ultimate limits of its effectiveness.

One of the things that worries observers most about Trump’s falsehoods is his particular reliance on conspiracy theory. His pick for national security adviser, Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, has made them somewhat of a specialty, endorsing even ones as ludicrously bizarre as the tale of the Satanic Democratic pederast pizzeria, a concoction that almost ended in tragedy when an armed man went to verify the rumors. It is bizarre to hear adults, especially ones who will likely soon be in charge of national security, discussing these fairy tales as if they should be taken seriously.

When falsehood invades the highest offices in the land, it forces the population into a surreal doubleness where there are two sets of memories, two account books, two realities that must be contended with. This chokes those who want to operate through a legal framework, according to the rules, since the rules now apply to a fantasy; a complicated strategic triangulation is always necessary to produce a real result. Opponents have to struggle continually with cognitive dissonance.

As an example: Stalin’s purges of the late ’30s were predicated on outlandish conspiracy theories—in particular, a tale of a vast anti-government network bent on his assassination. No such conspiracy existed, perhaps unfortunately. Nonetheless, some 8 million people were arrested on this pretext across the Soviet Union. They were tortured by the secret police in basements and forced to admit to crimes they had never committed. Most were sentenced to exile in remote work camps; roughly 1 million were shot.

What’s important here are not the horrific numbers. (Though it’s important to remember the traumatized history of that society when we consider Russia’s current geopolitical stances. The parents and grandparents of the present power players lived through this tragedy, and it left its mark and impress on the whole electorate and their machinery of government.) In this context, it’s merely important to note that easily disproved lies are capable of creating havoc on that kind of scale.

There was little concern for credibility in the accusations of Stalin’s minions or in the lies the victims of the purge were forced to tell in court before their executions. Even in the notorious show trials, designed to prove the legitimacy of the purges to the world, there was a laziness about the regime’s fabrications that revealed their arrogance. Imprisoned “spies,” stammering out the lines they’d been fed by their torturers, confessed to flying overseas for meetings, but the airstrips they said they flew in to were no longer open; the hotels where they said they rendezvoused with fellow operatives had been demolished decades previously. Lives hung on lies that could be seen through with any simple fact check.

The evidence was not credible, but it was designed to tell a good story—because that was all that was needed to convince a visible portion of the public to bay for execution. The bulk of the public stayed silent, and, bewildered, simply switched out the chromotype portraits on their walls of Communist Party officials who had been liquidated. The disgraced dead were erased from photographs of earlier Party triumphs. The message to the population was clear: Revise your memories. There is now a new past.

Stalin’s omnipresent slogan during this period was itself a miracle of bald-faced lying: “Life is getting better, comrades! Life is getting merrier!”

As the victims of the purges heard the list of impossible charges made against them, they often murmured that it was like being in a dream they couldn’t wake from. They saw friends accuse them of absurd and monstrous crimes. Of course it was dreamlike: They were being forced to maneuver in a real legal system based on false premises. They had to negotiate plea bargains in a situation where the truth itself was specifically inadmissible. Their lives oozed out of the jagged crack (as the logicians would have it) between the correct and the true.

It’s important to remember this: A regime can work a population so that they don’t object to even the most bald-faced lie. There is no safety in numbers, even vast numbers, if no one speaks up. Before we fall into the fantasies of liberal dystopia, however, it’s worth pointing out that Stalin had at his disposal an absolutely captive nationalized press. All information in print had to be sanctioned by the Party, which accommodated the complete pulverization of the real. There was a hoary Soviet joke about the nation’s two big papers, Pravda (“Truth”) and Izvestiya (“News”): “There is no truth in News, and there’s no news in Truth.”

It’s vitally important that this is still not the case in our American situation—though at the same time, we should recall that Trump has threatened the suppression of the press. Insofar as he has a plan for accomplishing this, it’s apparently through restricting official access, even within press conferences themselves, and perhaps more potently, plunging the press into financially exhausting litigation. Of course, any attempt to curb the free press would meet with stiff constitutional opposition. On the other hand, a captive press was not necessary to convince thousands of American leftists in the 1930s to take Stalin at his word and resolutely ignore evidence of the purges taking place within the USSR; nor has a restricted press been necessary to convince Trump’s followers to ignore fact in favor of slapdash fiction. (Recently, for example, more than half of Republican voters told pollsters they believed he’d won the popular vote in a “massive landslide,” though he lost by nearly 3 million votes.)

Putin’s Russia, meanwhile, still has one of the most stifled and policed press cohorts in the world. Putin’s regime doesn’t merely use the noose of crony capitalism to purchase and strangulate opposition; there is a terrifyingly high fatality rate among Russian journalists, and it seems likely that many of the contract killings, mysterious blows to the head, and spontaneous tumbles out of closed windows that they die from can be traced back to the regime. Trump has defended his pal Putin on this count, as on so many others. When asked to condemn Putin’s likely involvement in the killing of journalists, Trump essentially shrugged it off. He replied glibly, “Our country does plenty of killing also.”

Another important strategy in Stalin’s destruction of truth was the scapegoating of expertise. In his case, he focused his country’s ire on “bourgeois specialists.” During the period of his first Five-Year Plan (1928–1932), his disastrous program of forced industrialization and farm collectivization, massive failures in infrastructure and productivity had to be blamed on someone, and so his regime created the fiction of “wreckers,” often drawn as disgruntled middle-class industrialists who, now forced to work for the People, were quite literally throwing a wrench in the works. Wreckers supposedly put glass in the country’s butter; they were somehow responsible for a tick infestation. Meteorologists were purged because Stalin did not like the weather they were reporting—they were unable to ward off drought. In many cases, wreckers were blamed for the regime’s own malcoordination and malice amidst mass hunger and devastation. (The methodical destruction of truth means we will never know the full death toll due of the first Five-Year Plan, so estimates vary from 4 million to 10 million, generally settling around 6 million.)

There are three important elements to notice here in thinking about the lessons of falsehood: First, the tactic of blaming one’s own failures and crimes on an enemy, however laughable that accusation might be, is one that Trump has already undertaken with notable success—think, for example, of his complaint that it was Hillary Clinton, and not him, who started the whole Barack Obama “birther” story. Patently untrue, and yet this somehow did not discredit him. Stalin, of course, was infinitely more homicidal and nefarious: the murder of his friend and rival Kirov, which sparked the mass witch-hunt of the Great Terror, was almost certainly arranged by Stalin himself. But casting blame for the Trump administration’s own deeds and mistakes on an opponent is a tactic we will probably see used even more often in the coming years.

A second point: Stalin presided over the industrialization of his country, the flooding of workers into factories; Trump will, despite his wishes, be presiding over the other end of that process, as mechanization flushes human laborers out of factories. It’s a terrifying economic and cultural prospect by any standard. The real challenges for employees confronted with replacement by robotic labor will require some deft and quite fundamental economic re-thinking at the national level. We’re not likely to get that. Trump’s typical response is to blame off-shoring and immigrants, both historically dated explanations of job loss. Based on the Soviet example at the other end of the historical production line, we can expect these accusations to become even more virulent as the situation grows more desperate. As Trump fumbles that economic transition, we can assume that his opponents, both in Washington and on Main Street, will be cast as “elites” who are, supposedly, causing the problem in the first place.

This leads us to the third element: Trump, like Stalin, tends to tinge the idea of expertise with class resentment. The perennial deceptiveness of perceived “elites” is offered as an excuse to ignore and contest economists, diplomats, historians, scientists (of which more in a moment), political scientists, mainstream news, foreigners, and 17 U.S. security organizations including the CIA and the FBI. We should not forget that Trumpism is actually rooted in the middle class—despite mythology to the contrary, the Trump supporters who delivered the Republican primaries to the billionaire made considerably more per annum than either the national average or Hillary Clinton/Bernie Sanders supporters—and that college-educated block was actually just as important as a rural white working class in securing him the election. His Cabinet is stuffed with wealthy members of the elite—though, in their defense, they are notably lacking in relevant expertise.

Here lies another important parallel: Stalin cast aside scientific fact when it was politically irritating, dismissing it as another form of wrecking and elitism. Evolution in particular came under attack: the idea of natural selection didn’t accord well with Communist theory. Rejecting all evidence to the contrary, Stalin turned instead to the stunningly pseudoscientific theories of Trofim Lysenko, an agronomist who came from a suitable peasant background and who argued that acquired traits, learned traits, could be directly inherited. This was patently untrue, but that did not stop the Stalin regime from demanding that all scientists, regardless of their field, accept it as truth. When professional geneticists cried foul, Lysenko denounced them as cold-hearted brainiacs, “fly-lovers and people-haters” peering into their tanks of mating drosophilae, oblivious to the world of practical work. Scientists who objected to this crude fabrication and tried doggedly to stick to scientific reality lost their jobs, were arrested, and occasionally were even executed.

As a result, Soviet science was hamstrung for a generation. All work on botany and cell biology had to be carefully pruned and grafted to accommodate a complete fabrication.

The lesson here is clear not simply for the rejection of evolutionary science, but for Trump’s rejection of climate science (a hoax, we are told, cooked up by that sneaky Chinese government). But the physical world is unfazed by human lies. It operates according to its own principles regardless.

This gives some idea of the costs that can be incurred when truth is inundated by falsehood. The parallels are useful both for understanding the psychology of the nationalized lie and for glimpsing a worst-case scenario. But the worst-case scenario is exactly that, as we should remember before plunging ourselves into sensationalist panic. Trump seems most interested in kleptocratic plundering, a model of misgovernment very different than the mass murder of Stalinism. On the other hand, it’s hard to precisely calibrate an appropriate sense of disaster when the president-elect’s campaign promises (soft truths, to be sure) include locking up and inciting violence against his opponents, and rounding up and deporting millions of Americans based on national origin or religion. In the barrage of untruths, no one can tell which whoppers Trump plans to make good on. His unreliability is for this reason seen as a plus by his most humane followers, who tell themselves he has lied about the bad parts. It is also one of the things that destabilizes resistance to him—either by the left or the right.

I should close this discussion of Russian technique and starry-eyed American pupil by pointing out that eventually, Stalin was so swamped in narcissistic untruth that it became self-defeating. But it was not just defeat for him: Tens of millions suffered more acutely. He plunged the country into disaster several times and impoverished it for two generations. He did not make Russia great again, whatever current Stalin apologists may argue. He presided over a nation that was economically crippled by his own willful ignorance.

And his worst mistake was that he decided to buddy up to a meaner boy, a brighter bully, a better liar than him. In 1939, the world was astonished—Russian citizens among them—when Stalin forged a nonaggression pact with Adolf Hitler. But by 1941, Hitler was ready to invade the USSR. He gathered the largest invasion force ever seen in European history all along the Soviet border. Red Army soldiers reported the rumbling of tanks across the boundary waters. Hitler sent reconnaissance planes into Soviet airspace.

But Stalin believed that there was some kind of fraternity of bullies, some honor among thieves, some sort of mutual respect of the fist, and that Hitler would not break their pact. He thought he was wily and planned to surprise Hitler by breaking it himself in a couple of years’ time.

Stalin’s intelligence forces pleaded with him to pay attention to reports of an incipient attack flooding in from all over the world. Spies risked their lives to send him information about troop movements and invasion schedules. They sent him details regarding the exact day and hour set for the first blow. In response, Stalin wrote, “Perhaps you can tell your ‘source’ from the staff of the German air force to go fuck his mother. This is not a ‘source’ but a disinformer.”

And so, on the night of June 21, 1941, the German Wehrmacht poured across the Soviet border with almost no resistance. On hearing the first reports of violence, Stalin, deluded by the myth of his own power, his own eminence, his own wisdom, told the armed forces to stand down until further clarification. He blustered that it was a provocation offered by rogue German officers: “Hitler simply doesn’t know about it.” What followed was a slaughter. Within a few hours, half of the Soviet air force had been destroyed, most of their planes still sitting on the ground. Within 10 days, Russia had almost fallen. Stalin, on the verge of some kind of breakdown, despaired: “We’ve taken everything that Lenin made and turned it to shit.” It would take years and millions of lives to regain the ground lost in less than two weeks.

Now, as Putin gleefully greets a new American regime and an eager new friend in the White House, we should remember this story. To Republicans who “look past” Trump’s shoddy grasp on reality thinking that they will nonetheless profit from his plunder—you are playing a fool’s game. History tells us that relying on the continued goodwill of a vindictive, amoral narcissist is not a great long-term strategy. A leader so beguiled by his own lies that he starts to believe them is profoundly dangerous to the stability of the country and, given our reach, the globe. Our government needs to be in touch with reality. Forget ethnic and religious tensions if you will, forget the very real and irreversible environmental costs: Even economic interests will not be well-served by playing out fantasies in the real world.

As Stalin himself understood, when truth is gone, nothing is stable, and no one is safe.