We typically associate marches with social movements and political demands, not with scientific objectivity and neutrality. But on April 22, Earth Day, scientists and “science enthusiasts” will march on Washington in a show of support for the scientific process. Responding to attacks on scientific expertise and threats to public funding, the growing protest of American scientists might also suggest something about the perceived direness of the state of the world under Trump: If the scientists are organizing, then things must be really bad.

We rarely think of scientists as political dissidents. But here, at the end of Black History Month, we would do well to remember a little-known history of science activism in the United States, one that stretches back to the antebellum era. American science itself has long discounted the scientific expertise and knowledge of African as well as indigenous peoples, while liberally extending the title “scientist” to Euro-American men who lived long before the term even came into usage in the 1830s. We further tend to associate the civil rights movement with transformations in society and politics, but it was just as much defined by the struggle to desegregate hospitals, and later with the health activism pioneered by the Black Panther Party. This history is often ignored, but it is a critical part of the picture if we are going to understand how science, access, and activism have been linked in the past.

Even before the modern civil rights movement, in the pre-Civil war era, black abolitionists used science to bolster their activism in the struggle for emancipation, even as most of them were excluded from scientific training. At that time, there were actual studies that purported to suggest that freedom—not slavery—shortened the life spans of black Americans. It was New York physician and abolitionist Dr. James McCune Smith who produced the statistical data that debunked those studies. Smith also happened to be the first black American to hold a medical degree and open a medical practice in the U.S., which he did starting in 1837—though he received his degree from the University of Glasgow in Scotland. (Racial discrimination barred his admittance to a medical school in the United States.)

Black nationalist and writer Martin Delany delivered scientific lectures while he traveled the country in the early 1850s. He wove lessons on astronomy and navigation into his 1859 novel, Blake; or, the Huts of America, to help enslaved people and their allies map out routes to freedom. Delany’s own political awakening followed from his abrupt ejection from Harvard Medical School after students and faculty protested his enrollment in 1850, along with two other black men and one white woman admitted into the program. In defiance of the decision, Delany took the title of “doctor” anyway.

Educator and abolitionist Sarah Mapps Douglass taught physiology and anatomy to generations of black American girls and women in Philadelphia. Because of the absence of visual aids and textbooks that positively represented women of color, she taught her students to use their own bodies as anatomical models. Douglass had taken courses at the Female Medical College in Philadelphia but did not graduate with a degree. She and Delany used the relative privilege of their—albeit “arrested”—medical training to share knowledge and resources with black American communities.

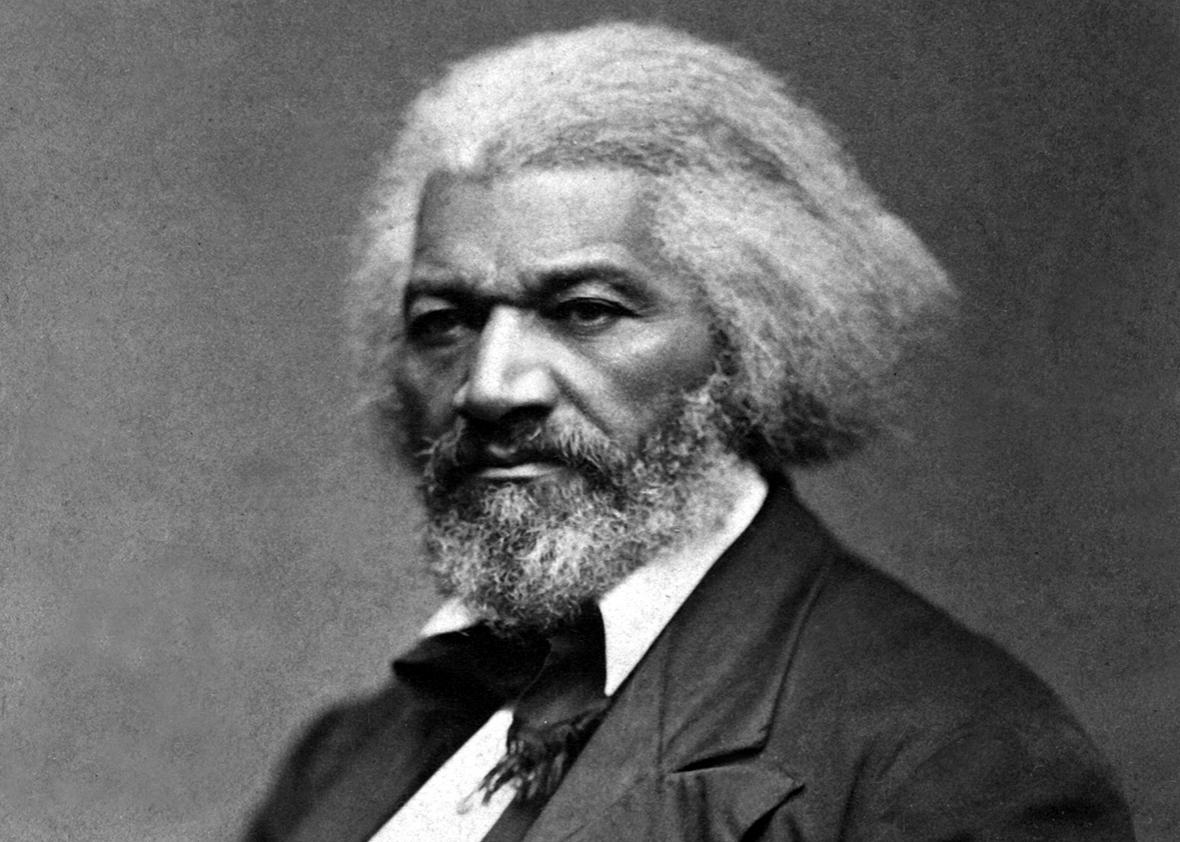

While Delany and Mapps Douglass served as advocates for scientific training and knowledge within black communities, Frederick Douglass used his status as a prominent anti-slavery lecturer and activist to publically critique scientific racism. In 1854, he was invited to speak at Western Reserve College in Hudson, Ohio, by a student group. Rather than shirking from the controversy that surrounded his invitation—he was, after all, a former slave addressing a graduating class while slavery remained “business as usual” across the nation—Douglass used the opportunity to present a searing critique of antebellum ethnology, a notorious school of scientists and doctors who provided “proof” of black inferiority for pro-slavery ideologues and politicians. Douglass was especially critical of the promotion of polygenesis: the idea that the races of humankind emerged in separate creation events and with unequal capacities. His fiery speech, “The Negro, Ethnologically Considered,” was a bold political statement at the time.

Douglass was an engaged scientific reader and advocate. Though he was emancipated in 1846, he was not recognized as a full citizen and instead lived as a fugitive from the U.S. law. No “citizen scientist,” Douglass instead practiced what I call “fugitive science”—science practiced on the run. In delivering his Western Reserve speech, he held onto a strikingly utopian view of scientific innovation as a motor for global communication, social amelioration, and even a “means to increase human love.” Taking aim at how the “separate” and “unequal” doctrine of polygenesis ousted people of African descent from the very category of the human, he rebuked race scientists who dared to speak “in the name of science” while spewing bias and hate in their wake. Such theories, according to Douglass, were contrary to the egalitarian ideals of science itself. Douglass’ arguments would be later validated by Darwinian evolution, which confirmed a singular, not multiple, origin of descent for the human species.

Some scientists worry that activism like the march may discredit their work in an anti-science political climate. Others fear it will associate science itself with a radical fringe.

But the history of black science activism is a reminder that science has never been an exclusive endeavor. The platform for the march reflects this: In fact, you could go as far as to say that a science march is only imaginable today because of the organizing and public interfacing that scientists of color and others have already been doing. Instead of further narrowing scientific expertise and authority in the face of forces that seek to discredit science, sociologist Ruha Benjamin advocates for a more expansive and “humble approach to science-making that takes the time to incorporate our many social histories into a just and more equitable vision of the future.”

Perhaps more than anything else, scientists—and their supporters—should remember that there has never been a time when science was separate from politics. Science is itself embedded in systems of power. The highlighting of intersectionality and diversity in the march’s platform is laudable, but such gestures of inclusivity should not obscure science’s own relationship to structures of dominance and exploitation. This was the balance struck by black science activists in the antebellum era, and they were able to use science itself to critique the field’s flaws while remaining fierce advocates of a science oriented toward social justice. A lesson for our times, indeed.