You need no more than a passing knowledge of horror movie tropes to immediately recognize the opening scene of writer-director Jordan Peele’s horror satire Get Out. And you need no more than a passing awareness of the past five years’ news cycle—or what it’s like to inhabit a black body in America—to immediately recognize the way in which Peele cleverly repurposes those tropes. A young black man (perennial scene-stealer Lakeith Stanfield) walks down the dimly lit sidewalk of a quiet suburban street, fumbling around on his cellphone for directions to his destination. A white car suddenly appears and begins to creep alongside him, gently playing the 1939 novelty song “Run, Rabbit, Run” by English comedy duo Flanagan and Allen. Instantly, his defenses are triggered. “Nope. Not today,” he mutters anxiously to himself, turning back the other way. “You know how they like to do motherfuckers out here.” But, not unlike the black teen whose name became a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement, he can’t avoid trouble. A masked individual exits the vehicle, attacks, and drags him toward the car.

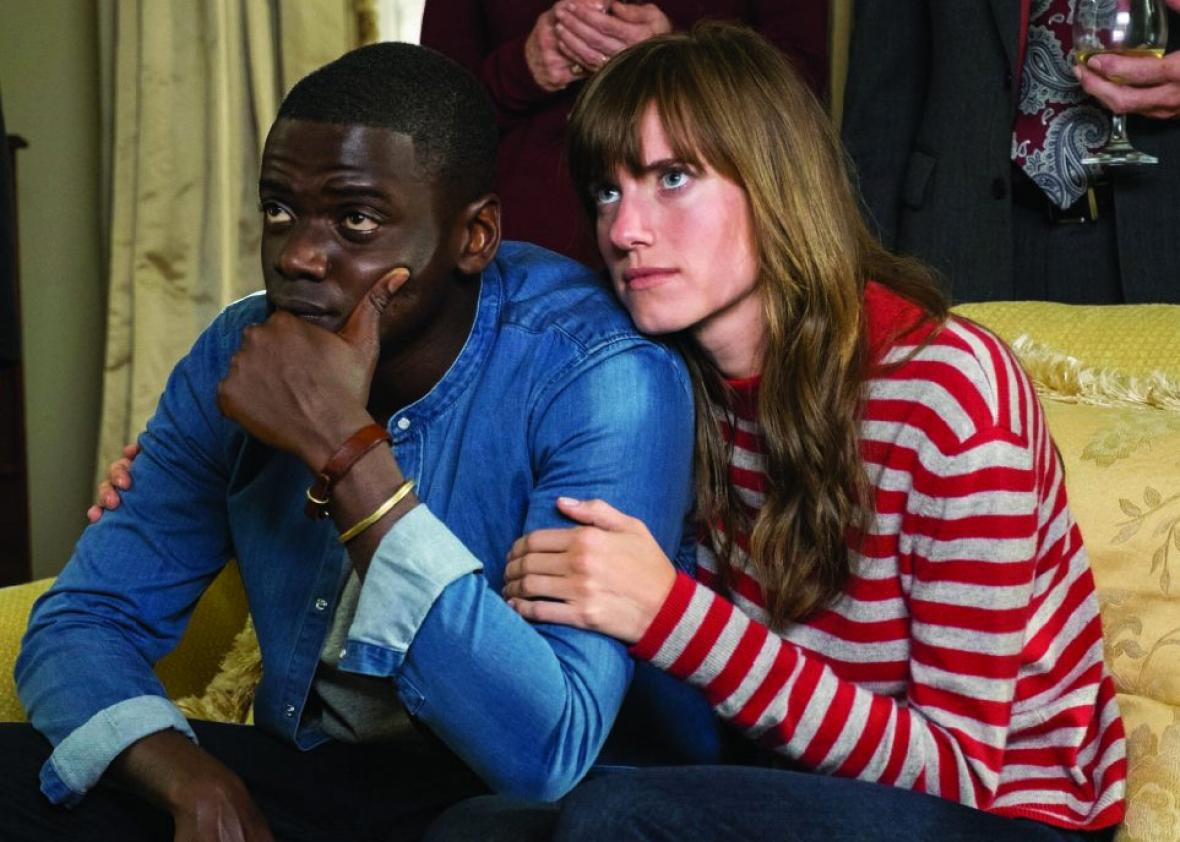

This is the essence of Get Out, which only grows more darkly relevant as the main story gets going, masterfully unfurling all of the real-life anxieties of Existing While Black while simultaneously mining that situation for all its twisted absurdity. Rising English actor Daniel Kaluuya stars as Chris, a photographer who is about to embark on a weekend trip in upstate New York to meet his white girlfriend’s family for the first time. This girlfriend, Rose, is played by Girls’ Allison Williams, whose on-screen persona as one of the foremost basic Beckys of the millennial generation has never before been put to such pitch-perfect use. And so it’s no surprise that Chris is a bit worried that she hasn’t mentioned to her parents that her boyfriend is black, or that she’s utterly oblivious to his concerns, insisting that “they are not racist.” (After all, she explains, her dad would have voted for Barack Obama a third time if he could have.)

If you’ve seen Rosemary’s Baby, The Stepford Wives, or Night of the Living Dead—all touchstones that Peele has cited as influences on his screenplay—you probably have a good idea of where things go from here. When Chris and Rose arrive, her parents’ estate is a mansion-size symbol of white affluence buried deep in the woods, while their zombielike black groundskeeper and maid seem to be possessed by the spirit of Uncle Tom. Peele puts the audience directly into Chris’ shoes as he navigates this new world that is at once utterly strange and all too familiar to him. He’s accustomed to the kind of casual racism tossed off by every white person he meets that weekend, whether it’s from Rose’s family or the prying guests that stop by for the family’s (initially) mysterious annual gathering. (“Is it true? Is it … better?” an older lady asks Rose immediately after fondling Chris’ biceps.) Yet he’s bewildered by the uncanny subservience of the only other black people he encounters. “It’s like they missed the movement,” Chris confides over the phone to his best friend Rod, a TSA agent, when he is able to slip away from the crowd. (As Rod, The Carmichael Show star Lil Rel Howery expertly serves as both comic relief and a surrogate for black audience members, warning Chris about the dangers of being around too many white people in an unfamiliar environment.)

Peele also draws inspiration from Stanley Kubrick, most obviously when the man in the opening scene compares the suburban streets to “a fucking hedge maze,” but also in the hallucinatory scenes in which Chris is placed under hypnosis by Rose’s psychiatrist mother (Catherine Keener), which feature images of Chris tumbling off into space that are soundtracked by micropolyphonic chanting reminiscent of the Györgi Ligety music Kubrick used in 2001: A Space Odyssey. But for all its nods to its horror forebears, Get Out, above all, wants to ensure that you walk away knowing that the black experience can still teeter on the precipice of being a nightmare, even in 2017. That even surface-level “admiration” for black culture on the part of white people can give way to insidious interactions that are, at best, a persistent annoyance black people must learn to laugh off, and, at worst, the kind of fetishization that only conceals deadlier preconceptions.

This tension is nothing new for Peele, who, alongside frequent comedic partner Keegan-Michael Key, mined this fertile territory repeatedly over five seasons of their hit Comedy Central show. Upon the release of last year’s Keanu, the duo’s sendup of both action-movie clichés and stereotypes about black masculinity, fans and critics wondered if the duo’s sharp wit, so tightly packaged in five-minute sketches, could sustain a feature-length film. Reviews were mixed and box office modest, though Keanu seems destined to become a cult classic. I anticipate that the fate of Get Out, which is Peele’s directorial debut, will be very different and will more closely mirror the massive cultural impact of Key & Peele. The movie currently holds a very rare 100 percent fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and at the packed screening I attended, the mostly black audience responded rapturously and knowingly throughout Chris’ ordeal. In hitting that sweet spot between scary and hilarious, and laying bare the many layers of America’s historic treatment of the black body, Get Out could soon land an enduring spot on the syllabi of many a college course, alongside both Rosemary’s Baby and Between the World and Me.