On May 15, the streaming platform Twitch began airing all 886 episodes of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, commercial-free, and it will continue doing so until the end of the month. While this slow, square children’s series might not have the same buzz as Master of None or the ripped-from-the-headlines relevance of The Handmaid’s Tale, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood is urgent television. If, for any particular reason, you’d be interested in watching a show about a man who accepts, embraces, and empathizes with his neighbors, effectively controls his emotions, lives a life imbued with imagination and radical kindness, and teaches us that “feelings are mentionable and manageable,” then I have a trolley you should catch.

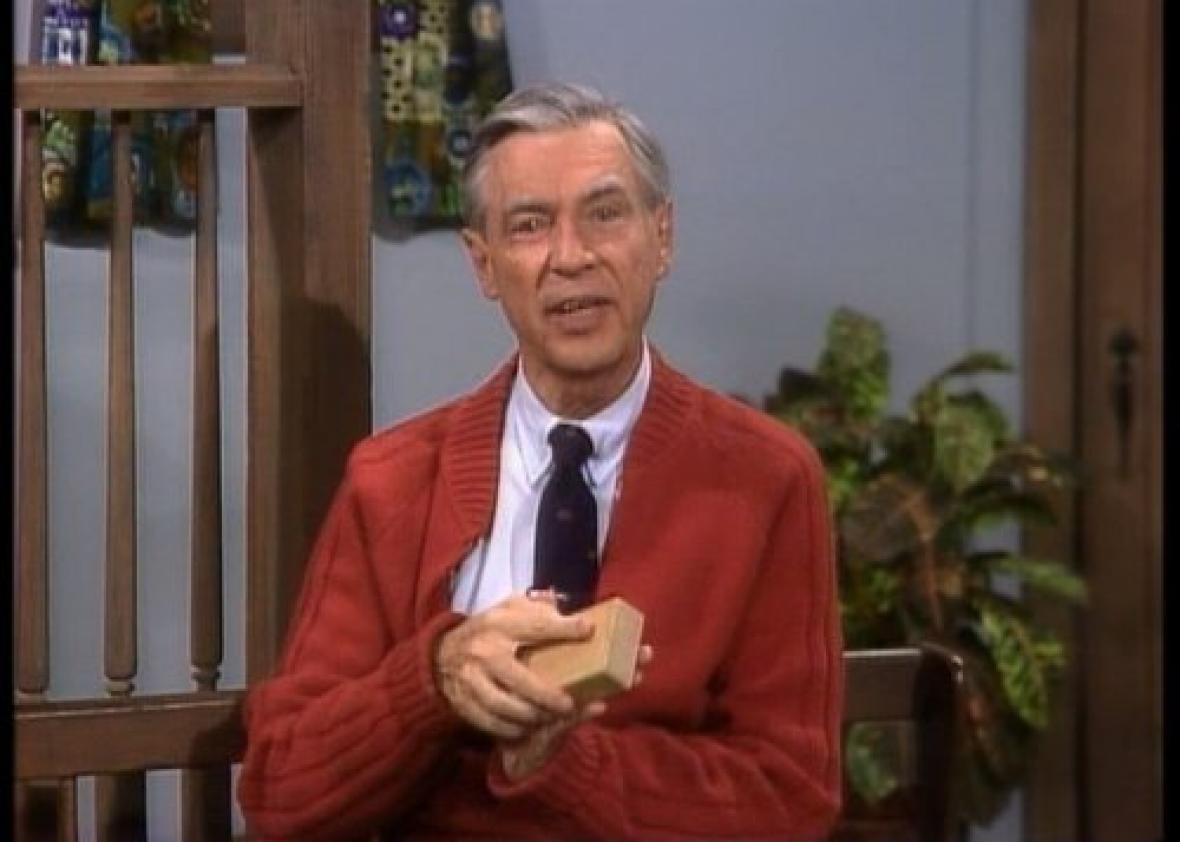

Starting in 1968, broadcasting on PBS from an alternate-universe Pittsburgh filled with jazz-guitarist handymen, unusually friendly postal workers, and a railway-accessible portal into a land of make-believe, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood came to define the experience of childhood in the second half of the 20th century. For all of its fanciful strangeness, there was always a graceful simplicity to the Neighborhood, an ease about growing up and learning that was mirrored in the leisurely way Rogers changed into his cardigan and Keds at the beginning of every episode. Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was educational programming, certainly, but, in its purest form, it was an emotional education. For 33 years, through Vietnam and Watergate and any number of other geopolitical catastrophes, Mister Rogers gave his viewers a language for expressing their feelings and a moral duty to care about the feelings of others. We could use a neighbor like him now.

And yet, since it went off the air in 2001, the neighborhood has been occasionally hard to find. Indeed, if you or the children you know have encountered Rogers at all in the last decade, it’s likely been through the auto-tuned, mildly annoying computer-generated antics of Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood. (The popular animated program is centered around Daniel Tiger, a peppy, cardigan-clad young tiger, who just happens to be the only begotten son of Daniel Striped Tiger, the shy, straggly cat puppet Rogers created for his Neighborhood of Make-Believe.) The show riffs off of a lot of old Rogers songs and ideas—Daniel sings snippets of the original series’ intro and outro tunes, the old puppets reappear as middle-aged parents, and the new neighborhood is littered with clever references to the original series from a crayon factory to an Uber-esque trolley—but its digital aesthetic is slick where Mister Rogers’ was homespun. While Daniel Tiger features many laudable innovations, including a far more diverse cast of characters than the original, there’s a big difference between a cartoon jungle cat and an earnest, adult human telling you that they like you just the way you are.

In the era of Daniel Tiger, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood exists primarily as a vague, sweater-swaddled memory for many viewers—at best a nostalgic artifact, and at worst, a piece of kitsch. Twitch has leaned into this characterization, promoting their stream by referring to the show as “retro content” that “taps into the appeal of nostalgic programming.” Netflix’s 2015 Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood “collection” suffered from the same reductionist impulse. The collection’s 20 episodes were curated less to provide access to a lost show than to locate its most meme-able moments, from the reveal of a comically primitive electric car to the awkward spectacle of Rogers learning how to break-dance. (An expanded, much-improved selection of episodes is now available on Amazon Video.)

Earlier this year, in the wake of President Trump’s dastardly pledge to defund the National Endowment forthe Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts, the video of Rogers’ stirring 1969 testimony before the U.S. Senate Subcommitee on Communications began to circulate again. The video had long been a favorite among YouTube aficionados, but Rogers’ emotional plea for public television—as well as the twist ending in which the gruff legislator’s heart grows three sizes—struck a new nerve. Here was a man at the beginning of the Nixon years, that era of world-historically bad feeling, rivetingly extolling the benefits of good feeling to the United States Congress. It was a powerful reminder of what thoughtful, passionate advocacy can accomplish, just as a new generation of advocates were feeling alternately empowered and imperiled.

To experience Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood as a series of viral videos or loving cover versions, though, is to overlook the unique and useful work that show actually did day to day for 33 years. That’s why Twitch’s stream, however cynically framed, is so revelatory. Watching even a few of these episodes in a row is to experience something that doesn’t feel like anything else in our media environment.

The world of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood is a world of gentle jazz, direct address, make-believe intrigue, and an overwhelming, almost uncanny, feeling of televisual love. As the man says, it’s a good feeling to know you’re alive. The episodes are grouped in themed clusters (the Amazon collection, while incomplete, makes a point of keeping these clusters intact), and the events in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe have sustained, serial narrative arcs, but what resonates most deeply is the way the show feels like a conversation between old friends. It’s a show cloaked in artifice—the aerial view of a scale neighborhood in the opening credits is an obvious, if friendlier, forerunner to Game of Thrones—but committed to audience byplay, or active participation in mundane and fantastical moments. You wouldn’t think that simply speaking words of support, love, and good intention directly into a lens would necessarily produce feelings of support and love in viewers, but that’s exactly what this show does. It’s the complexity of Mister Rogers’ feeling and the uncomplicatedness of its method that’s so striking, especially as an adult. Fred Rogers figured out that the best way to overcome the necessary mediation of television was to pretend that there was no mediation.

Mister Rogers’ neighborhood was, in many ways, a suburb, and, today, it retains the limitations of a typical suburb; it’s mostly white, conservative in its values, blandly Protestant in its sensibility. But the show’s emotionality was and is radical. The route to good feeling, for Mister Rogers, was empathy; the path to happiness was the control of anger; the climax of every episode was conflict resolution. It’s easy to mistake this as a nostalgic paean for a bygone era, to read a defense of this show as a modulated call to Make America Great Again. But Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood doesn’t represent another time so much as another way of seeing, another way of entering the world. The neighborhood is not an idealized version of American life; it’s a counterfactual experiment in imagining an American life that is founded in tolerance, kindness, and imperturbable calm. Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood debuted in 1968 to speak to children in an era of fear and anger and mistrust. This doesn’t seem nostalgic. It seems contemporary. It’s TV that hails you as a neighbor, and that tells you what to do with the mad that you feel right now.