On Monday morning, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Gill v. Whitford, a blockbuster case that could curb partisan gerrymandering throughout the United States. Shortly thereafter, the justices handed down two excellent decisions bolstering the First Amendment’s free speech protections for sex offenders and derogatory trademarks. While the link between these two rulings and Whitford isn’t obvious at first glance, it seems possible that both decisions could strengthen the gerrymandering plaintiffs’ central argument—and help to end extreme partisan redistricting for good.

The first ruling, Matal v. Tam, involves “a dance-rock band” called the Slants that sought to trademark its name. Simon Tam, the founding member, chose the name precisely because of its offensive history, hoping to “reclaim” the term. (He and his fellow band members are Asian American.) But the Patent and Trademark Office refused to register the name, citing a federal law that bars the registration of trademarks that could “disparage … or bring … into contemp[t] or disrepute” any “persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols.” (The same rule spurred the revocation of the Redskins’ trademark.)

Every justice agreed that the anti-disparagement law ran afoul of the First Amendment. They split, however, on the question of why, exactly, the rule violates the freedom of speech. Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts as well as Justices Clarence Thomas and Stephen Breyer, applied the somewhat lenient test for commercial speech, which requires that a law be “narrowly drawn” to further “a substantial interest.” The trademark rule, Alito wrote, is ridiculously broad: It could apply to such theoretical trademarks as “Down with homophobes” (disparaging beliefs) and “James Buchanan was a disastrous president” (disparaging a person, “living or dead”). The law, then, “is not an anti-discrimination clause,” Alito concluded. It “is a happy-talk clause,” one that is far too sweeping to survive constitutional scrutiny.

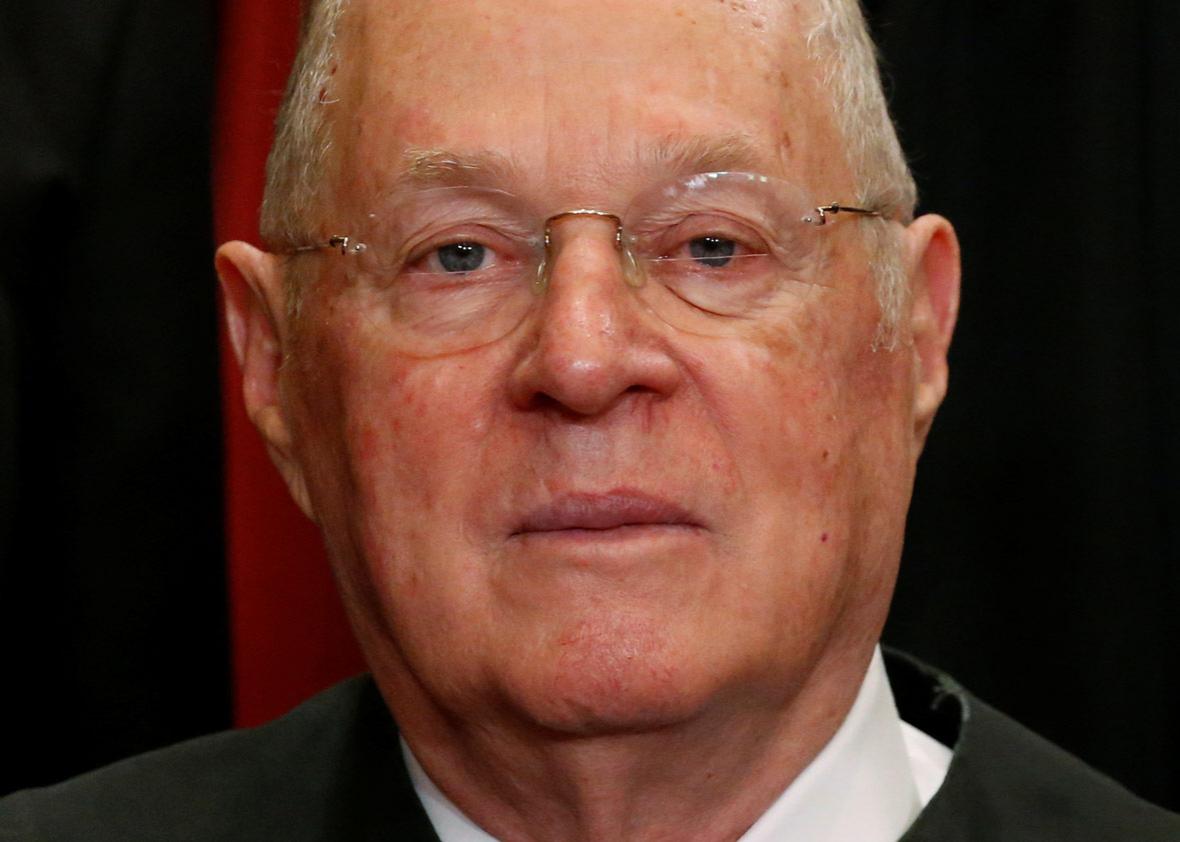

Justice Anthony Kennedy perceived even more insidious censorship at play. In a concurrence joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan, Kennedy wrote that the measure in question constitutes “viewpoint discrimination”—an “egregious” form of speech suppression that is “presumptively unconstitutional.” Under the First Amendment, Kennedy explained, the government may not “singl[e]out a subset of messages for disfavor based on the views expressed,” even when the message is conveyed “in the commercial context.” The anti-disparagement rule does exactly that, punishing an individual who wishes to trademark a name that the government finds offensive. “This is the essence of viewpoint discrimination,” Kennedy declared, and it cannot comport with the First Amendment.

A similar rift opened up between the justices in the second free speech case of the day, Packingham v. North Carolina—another unanimous ruling with split opinions. (Justice Neil Gorsuch did not participate in either case, as oral arguments came before he was confirmed.) Packingham involved a North Carolina law that prohibited registered sex offenders from accessing any social media website, including Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter. The language of the statute is so sweeping that it also barred access to websites with commenting features such as Amazon and even the Washington Post. In essence, the law excludes sex offenders from the internet. North Carolina has used it to prosecute more than 1,000 people.

Kennedy, joined by all four liberals, subjected the law to intermediate scrutiny, asking whether it “burden[s] substantially more speech than is necessary to further the government’s legitimate interests.” He easily found that it did. The “Cyber Age is a revolution of historic proportions,” Kennedy wrote, and “social media users … engage in a wide array of protected First Amendment activity on topics as diverse as human thought.” Our interactions on the internet alter “how we think, express ourselves, and define who we want to be”; to “foreclose access to social media altogether is to prevent the user from engaging in the legitimate exercise of First Amendment rights.” The North Carolina law therefore suppresses too much expression and is thus in contravention of the Constitution.

In his ode to social media, Kennedy proclaimed that the internet has become “the modern public square,” the 21st-century equivalent to those “public streets and parks” where the Framers hoped Americans would “speak and listen, and then, after reflection, speak and listen once more.” (Kennedy’s prose remains distinctive as ever.) In a concurrence, Alito, joined by Roberts and Thomas, rejected Kennedy’s public square theory as “loose,” “undisciplined,” and “unnecessary rhetoric” that elides “differences between cyberspace and the physical world.” The three conservatives agreed that the North Carolina law swept too far but insisted that Kennedy’s opinion granted sex offenders a dangerous amount of freedom on the web.

So: What do these cases—both correctly decided, in my view—have to do with gerrymandering?

To start, it’s important to view gerrymandering through a free speech lens, one developed by Kennedy himself in 2004. When the government draws districts designed to dilute votes cast on behalf of the minority party, it punishes voters on the basis of expression and association. To create an effective gerrymander, the state classifies individuals by their affiliation with political parties—a fundamental free speech activity—then diminishes their ability to elect their preferred representatives. Supporters of the minority party can still cast ballots. But because of their political views, their votes are essentially meaningless.

Kennedy has called this a “burden on representational rights.” It’s also something much simpler: viewpoint discrimination. In performing a partisan gerrymander, the government penalizes people who express support for a disfavored party—much like, in Tam, the government penalizes those who wish to trademark a disfavored phrase. Both state actions punish individuals on the basis of their viewpoints: If you back the minority party, your vote won’t matter; if you give your band an offensive name, you can’t trademark it. And even though neither action qualifies as outright censorship, both restrict “the public expression of ideas” that the First Amendment is meant to protect.

Packingham also includes a subtler gift to the Whitford plaintiffs. In an aside, Kennedy compared the North Carolina law unfavorably to a Tennessee measure that bars campaigning within 100 feet of a polling place. Unlike the North Carolina law, Kennedy explained, the Tennessee statute “was enacted to protect another fundamental right—the right to vote.”

Perhaps this passage is just more “loose rhetoric”—but I doubt it. Fundamental rights receive heightened protection under the Constitution. And although most Americans would probably agree that voting is a fundamental right, the Supreme Court has been cagey about saying so and inconsistent in safeguarding it. When the court upheld a voter ID law in 2008, for example, six justices paid lip service to the “right to vote” even as they shredded it; only the dissenting justices noted that the right is “fundamental” under the Constitution. Similarly, when the court’s conservatives gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013, they did not call the right to vote “fundamental.” Instead, they celebrated the “fundamental principle of equal sovereignty,” an archaic and discredited states’ rights doctrine. The upshot of that decision seemed to be that states’ rights are fundamental but voting rights are not.

Kennedy voted to uphold the voter ID law and kneecap the Voting Rights Act. But the justice is always evolving, and his aside in Packingham reads to me like a renewed commitment to the franchise set in the free speech context. If so, that’s terrific news for opponents of partisan gerrymandering. Such gerrymandering limits an individual’s fundamental right to vote (by making her vote useless) on the basis of her viewpoint (that is, her support for a political party). In effect, the practice attaches unconstitutional conditions to both voting rights and free speech, putting many voters in a quandary: They can either muffle their political viewpoints and cast meaningful ballots or express their political viewpoints and cast meaningless ballots. The Constitution does not permit states to punish individuals for exercising their rights in this manner.

Unfortunately, these tea leaves do not indicate inevitable doom for partisan gerrymandering. Kennedy recently indicated concern about judicial intervention into the redistricting process, and in the past he has questioned whether courts can accurately gauge which gerrymanders go too far. The Whitford challengers believe they have the right tool to measure partisan gerrymanders, a mathematical formula called the efficiency gap. Nobody yet knows if Kennedy will agree, and the justice has sent mixed signals—it’s worth noting that he joined the court’s conservatives in voting to stay the lower court decision in Whitford while the justices consider the case. (The court had ordered Wisconsin to redraw its maps.)

Still, Monday’s decision indicates that Kennedy and the court are, at the very least, moving in the right direction on the issues at the heart of partisan gerrymandering. Free expression and association aren’t really free if the government can punish you for your viewpoint by ensuring your ballot doesn’t matter; the right to vote isn’t fundamental if it can be diluted on the basis of political affiliation. The basic First Amendment principles Kennedy espoused on Monday explain why the court may well curtail partisan gerrymandering next term. In fact, they explain why the Constitution demands nothing less.