The rental crisis has grown so severe that some states have virtually no affordable apartments available for the lowest-income families, according to a new report from Freddie Mac, which finances loans for apartment buildings.

The report focuses on very low-income households, defined as those that earn less than 50 percent of the area median income. In rich areas, like New York City, a single renter could make $33,000 a year and be under that threshold. In poorer regions, AMI is much lower.

Freddie Mac tracked apartments that had been financed twice between 2010 and 2016, a period of low wage growth, and found that their rents had risen rapidly. Nationally, apartments affordable to very low-income families dropped from 11.2 percent to 4.3 percent.

In some states the change was much more dramatic. In Colorado, apartments affordable to VLI households fell from 32 to 8 percent; in Texas, from 10 to 3 percent; in North Carolina, from 10 to less than 1 percent. In California and Florida, where the housing stock was already entirely unaffordable to VLI households, the decline in affordability hit low-income households—the next bracket up the income ladder.

This is backed up by national data in the annual report from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, which shows that, over the longer period between 2001 and 2015, the number of severely burdened tenant households (those paying more than half their income in rent) making less than $15,000 rose from 4.9 million to 6.5 million, and the number of families making between $15,000 and $30,000 with severe rent burdens rose from 2.1 million to 3.5 million.

What happened to all those apartments for people with very low incomes? Some of them are still occupied by very-low income households—nearly 40 percent of households with incomes between $15,000 and $30,000 pay more than half their income in rent, leaving them with little to spend or save. For households earning less than $15,000, that portion rises to more than 70 percent.

But something else happened to those apartments: They became the homes of people with low incomes, who couldn’t afford low-income apartments that had been taken by people with middle incomes. And so on. It’s a kind of cascading national process of gentrification. Low-income apartments are desperately needed, but if you don’t build market-rate apartments for middle-income residents, it’s still those at the bottom who get hurt.

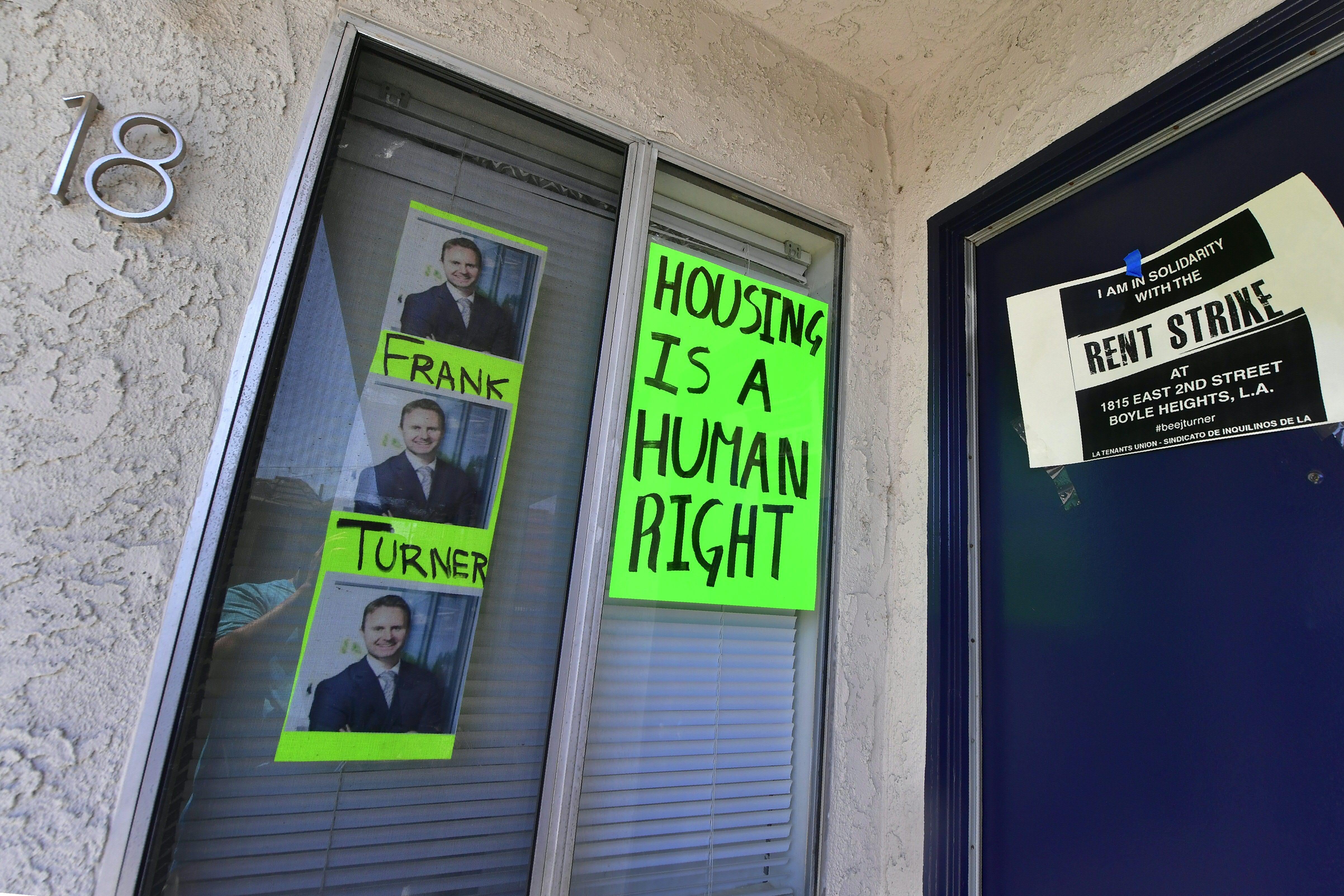

Ben Carson, the secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, has said the size of his budget doesn’t matter. But this data bolsters the case for greater federal involvement in housing assistance, by showing the severity of the crisis for poor renter households, only one in four of whom are covered by Washington’s current programs. Without them, if you live in Denver or Durham or pretty much anywhere in Texas, there simply is no affordable housing on the market.